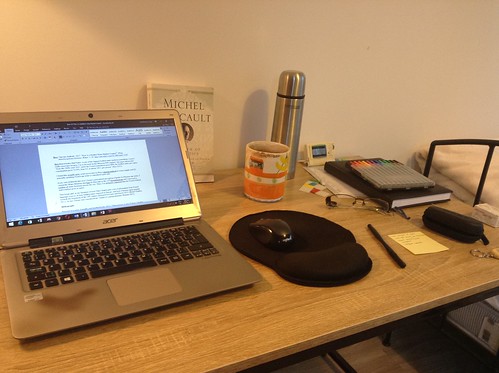

Anybody who follows me on Twitter or reads my blog will know that I am absolutely smitten with index cards. I have taken notes in index cards for decades, and I still do it. I loved index cards as a grade-school student and I adore them as a professor. I have a number of boxes to store my index cards. A few of those are portable, so you can take them with you, others are intended to stay at home. Index cards have been an intimate part of my life since I was too young to even write on them, and will continue to be an important element of my teaching practice, as I strongly believe that my students benefit from learning how to take notes in index cards, and the various methods associated with their usage. In fact, this 2020 I taught note-taking techniques using Index Cards and all my students have loved it.

Anybody who follows me on Twitter or reads my blog will know that I am absolutely smitten with index cards. I have taken notes in index cards for decades, and I still do it. I loved index cards as a grade-school student and I adore them as a professor. I have a number of boxes to store my index cards. A few of those are portable, so you can take them with you, others are intended to stay at home. Index cards have been an intimate part of my life since I was too young to even write on them, and will continue to be an important element of my teaching practice, as I strongly believe that my students benefit from learning how to take notes in index cards, and the various methods associated with their usage. In fact, this 2020 I taught note-taking techniques using Index Cards and all my students have loved it.

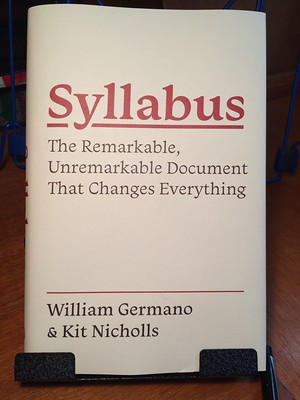

There are numerous strategies to take notes with index cards, but perhaps the most famous is Niklas Luhman’s Zettelkasten, which has recently been made popular again by Dr. Sönke Ahrens, who wrote one of the most authoritative texts on the method. Full disclosure: though I bought and paid for Ahres’ book on my own dime, I actually do NOT use Zettelkasten, as my Twitter thread explains.

I heard of, and learned something similar to the Slip-Box Method when I was in grade school. I think what happens is that we all end up modifying it to suit our own needs. But the same principles remain: you’re always writing, you need a permanent medium to record your thoughts.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 29, 2018

I heard of, and learned something similar to the Slip-Box Method when I was in grade school. I think what happens is that we all end up modifying it to suit our own needs. But the same principles remain: you’re always writing, you need a permanent medium to record your thoughts.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 29, 2018

Not to toot my own horn, but THAT’S PRECISELY WHAT I SUGGEST IN MY WEBSITE and to my students. I write memorandums https://t.co/hACSfxW6Y4 Synthetic Notes https://t.co/Xd9BgKtmBR – AIC extracts https://t.co/KljF5N1qml and systematize them in Excel Dumps https://t.co/LuNbAcwzhX

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 29, 2018

The reason why I made the Everything Notebook https://t.co/sVOjBFoE1g is because it’s sort of my Luhmann’s Slip-Box – all my notes in one place. You can obviously criticize me for keeping index cards OUTSIDE of my Everything Notebook. But I store everything in the same place.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 29, 2018

Addendum to my 2018 thread on Sonke Ahrens’ “How to Take Smart Notes”. The first time I read it, it was very hard for me to absorb. It took me FOREVER.

HOWEVER…

I just re-read it this past weekend and it was an absolute breeze. It took me less than 45 minutes to finish it.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 9, 2020

Bottom line: I DID enjoy this book and recommend it though I really do not like the Zettelkasten method as is. Hope my reading notes are helpful to someone.

To note: I do NOT do Zettelkasten.

I do a combination of my own approach to Index Cards https://t.co/RppZJmbPiz

Plus Peggy Boyle Single’s approach https://t.co/ze7NKGMQNC approach plus Umberto Eco’s approach https://t.co/hzTgyQovSD

I do NOT like the Zettelkasten approach.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 9, 2020

As someone who LOVES index cards, and who is a Virgo, Type A, Upholder (Gretchen Rubin) you might wonder what I do NOT like about Zettelkasten.

I do not like the sequencing approach, nor the “unique key”.

HOWEVER…

I think reading Ahrens’ book is EXTREMELY VALUABLE/HELPFUL.

Ahrens’ writing keeps me engaged and without de-emphasizing Zettelkasten, he extols the virtues of note taking and of index cards.

Plus the way he organized the book is just simple and elegant (see table of contents) pic.twitter.com/sUVhKK3FHc

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 9, 2020

DISCLOSURE: I bought and paid for this book on my own dime, as I do with ALL my books.

Recent Comments