The Spring 2021 term is coming upon us quite fast, and I have wanted to write a thread on how to prepare for a graduate-level seminar. I know the range of difficulty of readings, amount/volume/number of pages assigned is going to vary, but I’ve been thinking about this issue for a very long time. Personally, I reduced the number of readings that I assigned in my courses, but not everyone is doing this, and I strongly believe that we need to prepare students for whatever comes their way (including a reading-heavy course/seminar).

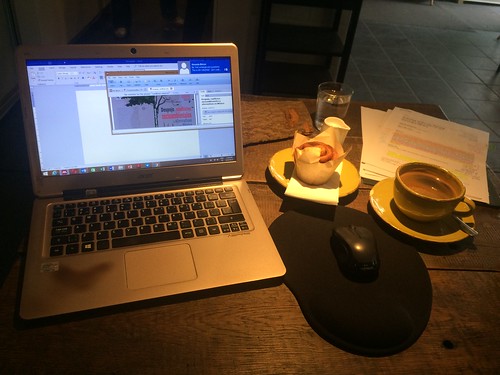

I am going to assume a course workload of 4-5 courses per week (exactly what I took when I did my PhD at The University of British Columbia), regardless of whether it is Masters’ or PhD. When I was a doctoral student, I took several courses across disciplines and faculties. I prepared each class the day before, over the course of a morning or an afternoon (I am terrible at night, and work better earlier in the day.

I am particularly worried/concerned for/thinking about my students who may take reading-heavy courses over the next few months, so I decided to write a thread showcasing how I prepared when I was a graduate student. In the process of writing the Twitter thread that this blog post draws from, I also provide some guidance on how to craft syllabi that while reading-intensive, can also be helpful to students by providing guidance on how to approach the reading material.

I remember very distinctly taking a class with Dr. Terre Satterfield on Science, Values and Policy and thinking “oh wow, each week has a theme!” (remember, although I have two brothers with PhDs and my Mom has a PhD, there’s a lot I didn’t know about the #HiddenCurriculum). I want to share my approach to syllabus design, because to help students discern strategies for how to read their assigned materials, I also need to read other professors’ syllabi, and deconstruct them so I can understand their choice of reading materials.

Below is my approach to designing syllabi.

I remember very distinctly that Dr. Satterfield always told me to look at the readings as a whole: “what do these readings, in their entirety, tell you? what’s the coherent story/narrative?”

This key question has helped me both prepare for seminars (as a doctoral student), and refine my syllabi (as a professor). Usually faculty write their syllabi offering suggestions on how to approach the readings. But in case they don’t, I always recommend that students look at the entire week’s block of reading materials and search for the key theme/narrative/story.

So how does this “searching for the key narrative/story/themes” approach work in practice? Below, I explain it in detail using examples from my own syllabi and those of other scholars I found useful for my purposes.

As you can see, I assign 4 readings per week (30 pages per, about). What would I do, if I were a grad student taking my seminar? I would devote an entire day/morning (depending on how fast you read) to reading, taking notes and systematizing my notes. When I was doing my PhD I prepared for seminars the day before (hard to do if you take 2 seminars same day, but advisable!)

For a second round, I suggest looking to see how each reading connects with one another. For example, for the week on extractivism, urban political ecology, these are the themes I would be looking for:

– accumulation by disposession (David Harvey)

– primitive accumulation (Marx)

– urban political ecology: scale, power differentials, cross-scalar dynamics, urban contexts

– how water is extracted, implications that this extractivism approach has (denial of the human right to water, etc.)

Asking questions off assigned readings helps make sense of them.

Other examples:

Having read a few of these previously (I studied Science and Technology Policy for my Masters), I can see what are the major themes of Dr. Rhode’s first week:

– artifacts are political (Winner)

– technology has associated risks and responsibilities (Wetmore, GHSA)

– S&T consumers

When I was a grad student, I found that if I asked myself Guiding Questions that helped me make sense of a coherent narrative helped me learn better. I also looked for themes, keywords, patterns, logics and debates (point-counter point). What do this week’s readings tell me? What’s the professor’s intent in assigning these readings? What do they want me to learn? Which are the key ideas, concepts?

To summarize, and clarify:

My Twitter thread and post were originally NOT about syllabus design (though I do provide detailed suggestions on how to design a syllabus, in a way that helps your students prepare), BUT about how to prepare for a graduate seminar – or an advanced undergraduate), as a student.

Here are the insights that faculty members can probably draw from this thread:

a) Design your syllabi creating discrete units that have Guiding Questions to help students make sense of the readings, and

b) Develop your syllabus using storytelling methods to create narratives.

And here are the insights I wanted students to absorb:

a) I recommend dedicating an entire morning/afternoon (or full day) to reading, taking notes, systematizing them and then writing a memorandum (a day before the seminar)

b) If you have 2 seminars on the same day, split time.

(Dr. Neff’s syllabus is here)

Now, how do *I* as a professor prepare to teach graduate seminars?

I do it the same way I prepared for seminars when I was a doctoral student. I dedicate time the day before I teach (since it’s a seminar, I lead the discussion more than “lecture”). I build a set of Guiding Questions and when I start the week, I provide an overall description of the narrative and the key concepts I want my students to draw from the readings. I then lead the discussion and engage with students asking them Prompting Questions based on the Guiding Questions.

Anyways, I converted my Twitter thread into a blog post, because I know my undergrad and graduate students will be taking seminars next semester and I want them to be well prepared. I do hope faculty and students both may get some good insights out of these tweets.

Recent Comments