A lot of people use my blog posts as guides to literature reviews, either for themselves or for their students. A lot of people use my blog posts as guides to literature reviews, either for themselves or for their students.

If you are a frequent reader of my blog, you probably know I’ve written a metric tonne of blog posts on specific items of the literature review (when to stop reading, how to create a mind-map of the literature, how to produce paragraphs of the lit review, etc.)

I understand these students’ concerns. Why should I be writing a literature review, what is its purpose and how do I go about it? After teaching undergraduate, and graduate (Masters, PhD) courses for a few years now, I think I understand the difficulty of understanding LRs.

What I have found most useful when I teach how to do Literature Reviews is explaining that to contribute to a body of research, we need to understand and know very well the landscape of scholarship that is out there. Like having a puzzle, and knowing where your own piece fits.

This universal, common understanding of what a literature review entails makes it easy to showcase methods and strategies across all three levels (undergrad, Masters, PhD). You are seeking to understand the big picture, and then narrow down your own topic to something manageable.

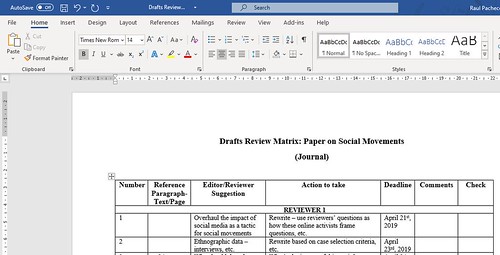

In that post, I explain that there are different ways to train yourself to do literature reviews. One way is to learn how to do annotated bibliographies and THEN move on to writing literature reviews. Another way is to learn how to create banks of notes and THEN do LRs.

Now, on to the typical question “when should I stop reading and start writing?”

HOW DO YOU PERFORM A LITERATURE REVIEW BASED ON MY BLOG POSTS?

Now, for the “live performance of how I conduct a literature review of a new topic”. My Grandma was a nurse, my Grandpa was a military doctor. Because of my poor health, and because I was obsessed with studying nursing growing up, I’ve spent a fair amount of time in hospitals. Because of COVID19, and also because I’ve recently recovered the friendship of a dear friend of mine from grade school who now is a Professor of Nursing and has a PhD, I’ve started thinking more about the politics and public policy aspects of understanding hospital operations.

I had been thinking about whether one could understand how health care professionals make decisions for a very long time. After all, I’ve spent a substantial amount of my life talking with doctors and nurses. And I’ve also cared for ill people (particularly my family). As someone who teaches Qualitative Methods, who has edited the International Journal of Qualitative Methods, who has published on ethnography and conducts ethnographies all over the world, I’m not unfamilar with the method at all.

HOWEVER I’VE NEVER done or studied hospital ethnography (until now, obviously). I recently wrote a grant proposal that, if funded, would allow me to conduct hospital ethnography across different sites/facilities/cities. I am not a health care professional, nor a medical anthropologist, so I would definitely need to partner with my good friend to do this.

Here is the thing: I believe one step in preparing literature reviews that we don’t properly teach and that helps students get out of the writing rut is asking them to DEFINE THEIR TERMS.

- Do you want to write on Street-Level Bureaucrats (SLBs)? First question: What is a SLB? Who are the key authors on SLBs? (I know this answer, we all start with Lipsky, the book I tweeted about earlier).

- Do you want to write on ethnography of illicit activity, such as drug trafficking? What is illict? How do we define illicit activity? How have scholars studied it?

Some Strategies to Generate Questions:

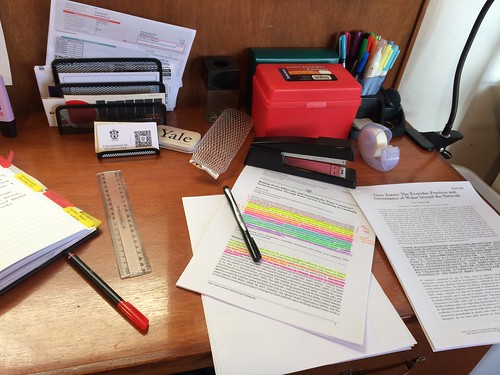

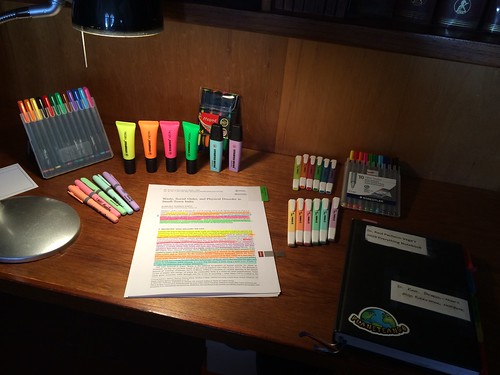

Now, on to the topic I’m researching right now: hospital ethnography. First step, as most of my blog readers will know, will be doing citation tracing, reading, annotating, systematizing, and writing memos until reaching concept saturation (and filling up rows of your Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump, CSED).

Below is a step-by-step performance of how I did Google Searching, citation tracing, CSED/memo writing, etc.

As I search for references, I link authors, concepts, ideas. Most of my mind-mapping happens in index cards.

Now, some instructions specific to educators:

Let’s get back to the actual process of doing the search/reading/reviewing the literature, and writing a memo.

As you can see, I am using “foundational” scholars to pivot around their scholarship and try to find new articles/improve my searches. Notice how I use Boaz’s, Van der Geest’s work to find OTHER articles that might be relevant, on hospital ethnography.

Now, this section describes how I REFINE MY GOOGLE SEARCH AND CITATION TRACING PROCESS. These refinements are necessary because I am not *just* writing about hospital ethnography but specifically, I am working on its application in Mexico. Thus I need to introduce keywords and refine my search, as well as track key authors.

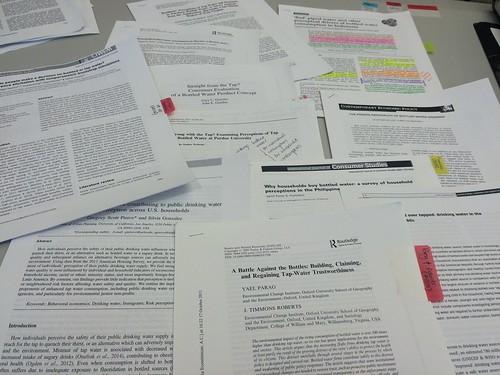

A key tip: if you are doing a first pass at the literature, I recommend downloading a bunch of articles to go through using Batch Processing.

MOVING FROM READING ALL THE THINGS TO WRITING THE LITERATURE REVIEW

While I don’t really have time to work on this literature review, I know that this is a key element of the review of the literature, and therefore I had to make some time to show the beginnings of how I would write the LR section of my paper/grant proposal, because that’s usually THE KEY jump that students struggle with. They all ask me: “Professor, how do I go from “I’ve Read All Things” to WRITING the Literature Review?”

Everything, EVERYTHING, literally everything in the research process is driven by the Research Question (and that’s why my students and research assistants always hear me harping about the importance of asking good questions and designing good Research Questions).

Now, it should be obvious by looking at my Mendeley library that I haven’t read, downloaded, and processed EVERYTHING that there is to read on hospital ethnography. But at least, I have the beginnings. If you were to do a LR, you should be well on your way. Should I find time in my schedule to finish this LR on hospital ethnography, I should be able to continue this process (search, process, synthesize, write) in a relatively seamless fashion.

When I have the time, or when I MAKE the time, I can continue thinking through everything I read on hospital ethnography, and every new citation that scholars recommend to me. I am crossing my fingers that this will all it make sense to you all (my readers) now. My hope that by performing a “live” LR using my own blog posts might help you too.

Recent Comments