A lot of people have asked me through the year how I accomplish as much as I do. While I feel enormously flattered, I don’t think I am particularly productive. What I am, is very disciplined. I learned early in my life that I had a really broad range of interests, and that if I didn’t rein in my own impulses, I would be scattered and disoriented before long. I knew I wanted to do academic research and that I wanted to complete a PhD and thus I needed to plan my life accordingly.

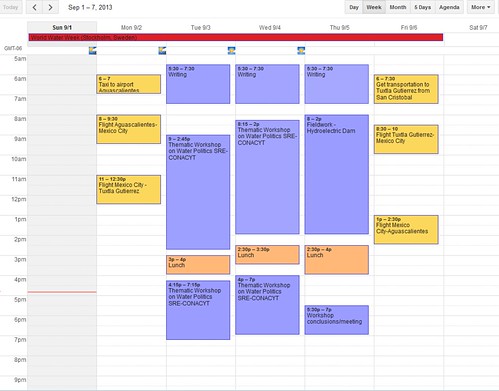

What you see above is my weekly template for the Fall 2013 semester (this is a term coined by Tanya Golash-Boza, whose blog I read religiously). It was nice to see a couple of other scholars (Eric Grollman and Jan in the Pan) write theirs. Even before I ever read Tanya’s blog, I learned to be organized with my life. I had a similar template for my life when I was a consultant and when I worked in the NGO world. My life is, and has always been, scheduled to the very minute. That was the only way I could play competitive volleyball, teach dance, do theatre, volunteer running literacy programs and teaching adults how to read and write, hang out with my friends, spend time with my family and still maintain a high average in school. All the while, of course, while maintaining sanity.

My schedule is online, and sync’d with my iPod Touch and with my HP TouchPad. This enables me to know what I am doing anywhere at any point in time. For years, my partner and I shared our online calendars, because that made it easier for him and for me to plan our time together. And I booked time for him that nobody else would every overlap with (that was, for me, the only way to maintain a healthy relationship). I follow the same philosophy when I book time for my friends and for my family, as well as for my own health. Nobody can schedule time for THEIR activities when it’s MY time. If you notice, I have left ample time for administrative stuff and for meetings during normal hours.

I am currently on a 1-1-0 teaching load, which is really very healthy and lucky for me. I also have a low number of students that I supervise, and my service commitments are limited too. I am the CIDE Region Centro representative to CIDE’s library, and I also sit on a search committee for a new tenure-track position, so my service does not take a lot of my time. I do have the Associate Editor commitments for the Journal of Environmental Sciences and Studies, and my regular contributions to editorial boards, peer reviewing and so on. But I don’t feel that they are terribly onerous.

I write better first thing in the mornings and I know that if I try to write on campus it will be much harder for me, so I wake up at 4:45am every morning, brew a pot of coffee and I start writing for 2 hours at least. Some of the time you see blocked for “Research” is also where I do a lot of reading and writing, so often times I end up writing for more than 10 hours per week. I also have scheduled time for “recovery” as my energy levels fall rapidly. This is something I knew about my physiology since I was a child, so I always schedule “down time”, otherwise my productivity falls.

On regular weeks I try to be in bed by 9:30pm at the very latest, except when I go out with my best friend from childhood and his wife (who both live in Aguascalientes as well – something that has turned out to help me keep my sanity). Two things I am desperately trying to fit into this schedule is regular volleyball training and frequent dancing, as I do miss those two components from my life.

Of course, academic conferences completely screw up this calendar, but I always try to ensure that at least I get exercise and regular writing in. I rarely attend academic events where the commitment is 12 hours per day or more, simply because I believe that allowing people to disrespect my time and my own schedule is a really bad idea. One exception I make is when my expenses are paid (as I feel a responsibility to the organizers).

A few caveats that I have to recognize:

- I have a low teaching load 1-1-0

- I am single (at the moment), with no children

- I have low service commitments

- Both my parents are academics, so even when I visit them on weekends I bring work with me

- Related: I love my research so I don’t care if I spend more than 60 hours per week on it. This means I often work on weekends and holidays (I try not to, though, at least not too often).

- I have a small army (5) of research assistants, who are incredible. This increases my productivity.

- I have an amazing set of collaborators all over the world, who are brilliant. They keep me honest and encourage me to work really hard.

- I have excellent resources both on campus (because I have a gorgeous office at CIDE Region Centro with a fabulous library and great access to online materials) and off campus (I live alone in a 3 bedroom, two story house, with a fully equipped home office, and I have a full home office at my parental units’ place too).

What I do hope sharing my weekly template with you will achieve is show you the broad range of activities you can engage in and goals you can achieve by being organized and schedule your life every week. This approach works, at least for me. And hopefully it will work for anyone who reads my blog.

EDIT –

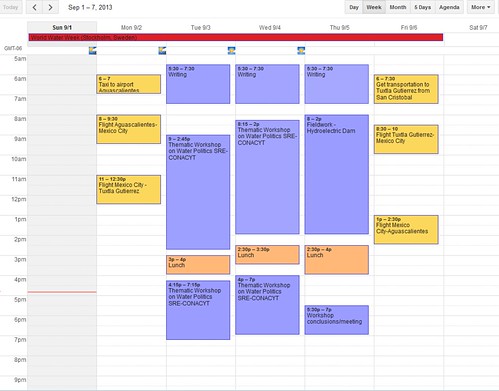

Lots of people have asked me “but what about when you have to go on the field, or when you have something unexpected come up, or at a conference?” so I thought I’d share my weekly template for the week following (e.g. September 2-6). As you will notice, I’m at an academic workshop all week, except for Thursday when I am doing fieldwork with the same group of water scholars. So, I only scheduled time to write every day, and nothing else. Because that’s the one thing that I want to keep doing regardless! Also, notice I didn’t schedule anything before or after my flights.

My schedule is rigid, I know. As Tanya herself said, I run a tight ship. But I am flexible enough to be willing to shift things around, particularly when the going gets tough. Self-care time does not actually get shifted in the sense that even if it’s an intense week for me, I always will take some time for myself, even if it’s not possible every day at the moment.

Recent Comments