Last year, I committed myself to a manifesto: Seeking peace and balance. In 2013, I launched new projects, assembled new datasets, and started teaching new courses. For me, 2014 was supposed to be the year where I would be able to balance my personal life with my professional (academic) life. This was a lofty goal given that I knew that my Fall 2014 teaching load would be relatively heavy compared to what I had before (I taught one new course, Regional Development, and one that I already had taught before, State and Local Government, but I revamped the syllabus completely).

In this post, I’ll summarize the lessons I learned for 2015 that I gained throughout the year. Given that the semester isn’t over, this post is still a bit premature, but I’ll be grading this week and finishing two projects, and I know for a fact that I will be too busy to actually think about what I learned in 2014.

The first thing I learned was that balancing my academic life and my personal life is and will continue to be very hard. Personal lives have an important impact on our academic lives. We aren’t robots who operate in a vacuum. We are humans who conduct research, teach, do fieldwork, mentor students, undertake service. This year, both my parents had episodes where they needed extreme care (three hospitalizations, two in the summer, one in late November). Since the reason why I left Canada was to be closer to my parents if/when they needed me, I figured I was lucky this time. Had I been in Canada at the time my parents needed medical care, I would have felt horrible and been terribly stressed. Still, I had to deal with a lot of stress, medical care, and individual care. Obviously, my own self-care suffered. I am very lucky in that CIDE was (and continues to be) incredibly supportive during these difficult times. Not only CIDE as an institution but also my co-authors, my colleagues, my students, senior faculty, everyone was and has been really helpful and understanding.

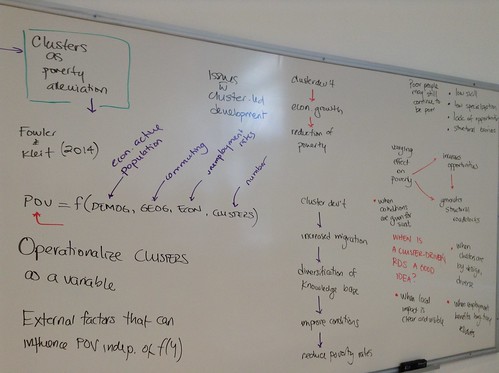

The second thing I learned was that it’s a really, really bad idea to do two new undergraduate course preparations in a semester, particularly when these courses are in a different language than the literature you would generally use. I asked to be able to teach again in English, and I was lucky that both my courses were earmarked as capstone and English-only ones. Teaching in English in a Spanish-speaking country has its own specific challenges, but it made me feel comfortable again, since the vast majority of my teaching has been in the English language (I taught most of my life in Canada).

A third lesson I learned is that it’s a really bad idea to try to balance travelling for conferences and workshops in a teaching semester. I piled all my teaching on Mondays and Wednesdays to be able to travel on Thursday and Friday, but then I found out that many conferences started on Monday, or were in Europe and I needed to use the entire week, which made me miss lectures. Thus I had to find a way to reschedule these missed classes which was a logistical nightmare. Luckily I have all my teaching in the fall so all the travelling I’ll be doing in the Spring and Summer 2015 will not affect my teaching.

A fourth lesson I learned was that all this travelling for workshops, fieldwork, talks, seminars and conferences was really being detrimental to my own health, so I started combining things. For example, when I went to Madrid for GIGAPP 2014, I ended up doing fieldwork for my informal waste pickers project. When I was in Paris for meetings at IHEAL-CREDA, I also used the remaining time to conduct interviews and do fieldwork for my remunicipalization of water supply project. I went to Washington DC for a climate evaluation conference, but I used the evenings to meet with other scholars with whom I am collaborating.

I also learned that trying to balance many projects and grants, trying to juggle many tasks will always require discipline and prioritization. I decided from the beginning of the year that I was going to try and do less service (although of course, as an Associate Editor of an international journal, and as a member of executive committees of several learned associations, I do much more service than I would probably do if I were not as involved in international committees) and that I was going to try to say NO much more often.

I also decided that I would no longer do book chapters (except for international, English-language ones, that I could circulate broadly), and that I would no longer publish in Spanish (except for two special issues of journals I’m coordinating, and a single-authored book I have under review). There are one or two book chapters that I committed to doing in Spanish that I can’t say no to (a particular research group on inter-basin water transfers in Latin America), but I decided that I want my scholarship to be internationally recognized, and let’s face it, even if I’m based out of Mexico, I’m required to publish in English. I already have plenty of publications in Spanish, so I don’t feel I need to do much more.

In the end, I am very happy with my productivity in 2014 in the face of the personal challenges I had, and I am sure that what I have accomplished is the result of discipline and daily writing practices, as well as prioritization. I will continue to zealously protect my time, given that I’m still pre-tenure.

Ultimately, I have also experienced setbacks (two particular manuscript rejections towards the end of the 2014 year were extremely painful), but as I have said before, each individual should have his/her own definition of what success in academia looks like. For me, 2014 was extremely successful and I look forward to a fantastic 2015.

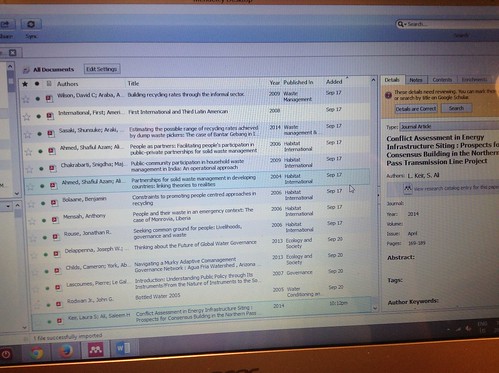

My production for 2014:

Peer reviewed journal articles:

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “The impact of Elinor Ostrom’s research on Mexican commons governance: An overview” Policy Matters. Issue 19. CEESP and IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. Pp. 23-34

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Ostrom y la gobernanza de agua en México” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 76(5):137-166.

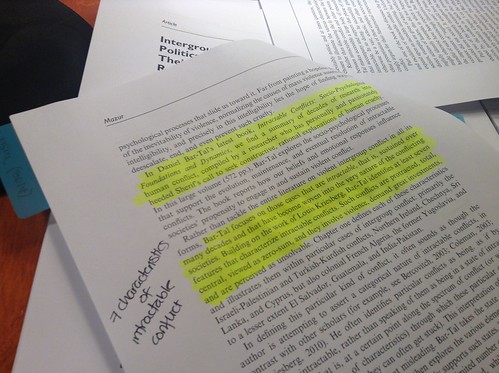

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014). “Conflictos intratables por el agua en México: el caso de la disputa por la presa El Zapotillo entre Guanajuato y Jalisco.” Argumentos. Estudios Críticos de La Sociedad, 74(27), 221–260.

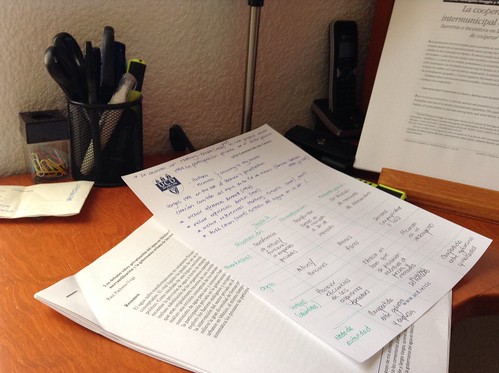

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Intermunicipalidad como un arreglo institucional emergente: El caso del suministro de agua en la zona metropolitana de Aguascalientes” Revista de Gestión Pública.

Peer-reviewed book chapters

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Conflictos intratables por el agua en México: Aplicando el recorte analítico de Intratabilidad, Enmarcamiento y Reenmarcamiento” (IER) In: de Alba, Felipe and Amaya, Lourdes (Eds.) “Estado y ciudadanías del agua: Cómo significar las nuevas relaciones.” Ciudad de México, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, pp. 279-317.

Non-peer reviewed book chapters

Raul Pacheco-Vega & Alberto Hernández Alba (2014) “Percepciones divergentes de la escasez de agua en León y Guadalajara: Un análisis del caso de la presa El Zapotillo” In Daniel Tagle (Ed.) La crisis multidimensional del agua en León, Guanajuato. Universidad de Guanajuato. Guanajuato, Gto. Mexico. Pp. 125-138.

Papers presented at conferences

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Tendencias mundiales en privatización y remunicipalización del servicio público del agua” V Congreso GIGAPP (Grupo de Investigación en Gobierno y Políticas Públicas), Madrid, Spain. September 29th-October 1, 2014.

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Polycentric water governance in Mexico: Towards a research agenda” Workshop on the Ostrom Workshop (WOW5). Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, June 18-21, 2014.

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “La gestión urbana del agua residual en Aguascalientes: Una mirada neoinstitucionalista a la privatización, el saneamiento y el reúso (2010-2013).” III Congreso de la Red de Investigadores Sociales sobre el Agua (RISSA). Salvatierra, Guanajuato. April 9-11, 2014.

Kate O’Neill & Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Exploring Models of Electronic Wastes Governance in the US and Mexico: Recycling, Risks and Environmental Justice” International Studies Association. Toronto, ON, Canada. March 26-29th, 2014.

Raul Pacheco-Vega (2014) “Gobernanza de aguas transfronterizas en América del Norte: Dimensiones de cooperación y conflicto en Seattle/Vancouver y San Diego/Tijuana”. International Workshop “Cuencas transfronterizas: espacios de expresión de lo politico”. January 15-17, 2014.

Recent Comments