I promised I would post the crib of my talk at the UNESCO Chair & Institute for Comparative Human Rights, as well as the slides. If you are interested in reading the tweetage coming from the conference, you can do so here too.

MY TALK:

I want to take this opportunity to thank the UNESCO Chair & Institute of Comparative Human Rights for inviting me to give a talk at their 16th Annual International Conference here at University of Connecticut. The conference focus, the Human Right to Water, is a topic that is near and dear to my heart, and one of the foci of my scholarship for a number of years now. Thank Dr. Bandana Prukayastha for chairing the panel and co-chairing the conference, Dr. Omaara-Otunnu & the organizers, staff and volunteers. Dr. Mark Healey – thank you so much for your generous giving of your time to host me, and Dr. Prakash Kashwan, thanks for your kind feedback and for attending and promoting my talks. Very grateful.

I am honored to be sharing the podium with two scholars and activists whose work I deeply respect, Professor Christiana Peppard and Ms. Candace Ducheneaux. Dr. Peppard’s research on global water ethics and Ms. Ducheneaux’s work on collaborative ecosystem restoration and rainwater harvesting techniques in South Dakota are both profoundly inspiring and I’m humbled and honored to be in their company here. Both of these amazing women work in areas that are often forgotten and their scholarship and activism highlight a commitment to the proper implementation of the human right to water in their respective fields.

My field of study (the global governance of water and sanitation) is also often forgotten, in particular the wastewater and sanitation side. This is regrettable since more than 2.4 billion people lack the dignity of access to a toilet. Yes, that is true. More than 1 in 3 people worldwide lack access to the most basic need a human being can have: relieving themselves from one of their most fundamental physical needs: excreting waste. More than 900 billion people still defecate in the open, and we missed the Millennium Development Goal on sanitation by at least 15 years. Despite having been recognized as one of the most important health discoveries of the century, the toilet is still shunned, and so is the need for access to them. Lack of proper sanitation has a disproportionately large negative effect on women and girls because of the potential for sexual violence against them in their search for private locations to relieve themselves.

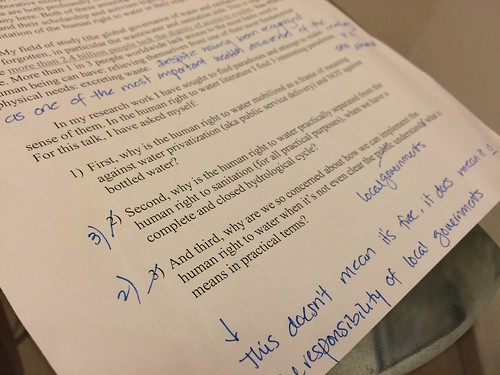

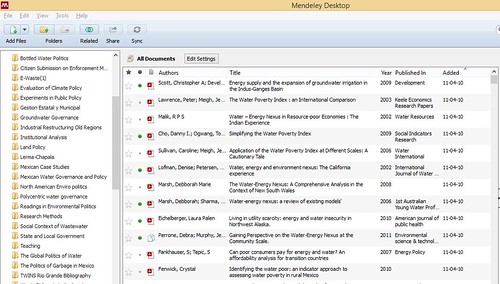

Most of my work has concentrated on the human and political dimensions of cooperative and uncooperative resource governance. My work on the human right to water literature has made two arguably bold and controversial but necessary claims. First, that ensuring global access to sanitation facilities is equally if not more important than access to clean water . And second, that bottled water as a global industry represents a threat to the global implementation of the human right to water. For this talk, I have framed my claims in the form of research questions I’ve been tackling, and I have added an additional one:

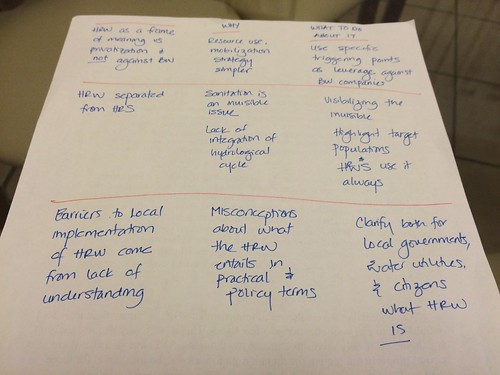

1) First, why is the human right to water mobilized as a frame of meaning against water privatization (aka public service delivery) and NOT against bottled water?

2) Second, why are we so concerned about how we can implement the human right to water when it’s not even clear governments at all three levels (and citizens) understand what it means in practical terms?

3) And third, why is the human right to water practically separated from the human right to sanitation (for all practical purposes), when we have a complete and closed hydrological cycle?

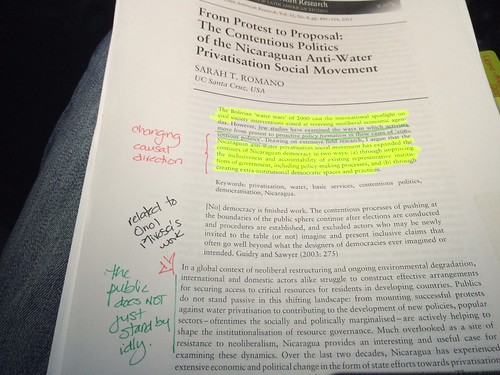

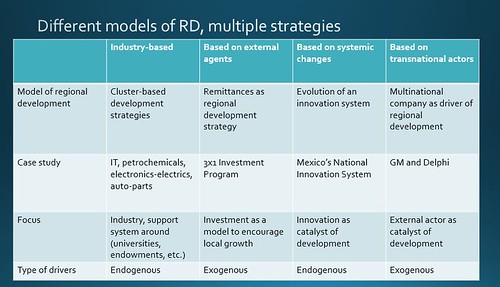

With regards to the first puzzle, I find it fascinating that Mexican activists have used human right to water as a conceptual and mobilizing frame for anti-privatization campaigns rather than anti-bottled water campaigns. In the last few years, the Mexican federal government has been pushing for privatization of water supply, even attempting to make it part of the new General Water Law proposal. This proposal was obviously quickly shut down, partly because of strong activist pressure, but also because of academics’ involvement in its analysis and subsequent critique. Anti-water privatization activism has been popular in Latin America, as demonstrated by Romano with the Nicaraguan case study (Romano 2012), Mirosa with the Bolivian example (Mirosa 2012), and Pacheco-Vega with the Mexican case (Pacheco-Vega 2015a). For a new research project, I have been following the protests against Nestlé in California in the US and British Columbia in Canada in order to compare strategic mobilizations against bottled water and against water supply privatization in North America. I find that mobilizing against privatized water utilities is conceptually and strategically simpler for activists rather than lobbying against the Goliath of powerful transnational bottling water companies. Strategically, anti-privatization activists face less resource consumption in the case of targeting private water supply than when taking on transnational corporations such as Nestlé and Danone. In my previous research on transnational environmental activism I have found that one of the best strategies to mobilize policy action has been to build transnational and global coalitions that put pressure on domestic governments (Pacheco-Vega 2015b, 2015c). Anti-privatization protests have been able to exert more pressure because of an increased global focus on, for example, the Irish and Detroit cases. There is a shared frame of meaning: all populations, whether rich or poor, have a right to water. But we still haven’t found as much of a homogeneous frame of meaning in the case of bottled water. However, as Sultana and Loftus encourage us when discussing water activism in their edited volume on the human right to water, “we have an obligation to build on such struggles rather than simply using them for our own intellectual debates” (Sultana & Loftus, 2012b, p. 18).

Secondly, it’s interesting that perhaps the challenge that government officials say they face is the domestic implementation of the international norm of human right at the subnational scale . I believe this is a problem that is derived from a lack of understanding of the notion of human right to water as a global norm and as a conceptual framework (Gerlak and Wilder 2012; Gupta, Ahlers, and Ahmed 2011; Hall, Van Koppen, and Van Houweling 2014; Meier et al. 2014; Salman 2014; Schmidt 2012; Sultana and Loftus 2012a). On the regulatory challenge of implementation and building a new regulatory framework for the human right to water, I argue that while in 2007 we could say (and Karen Bakker in fact did) that the legal grounding for the human right to water was shaky, that’s not the case anymore (Bakker 2007). The international norm on the human right to water was effectively implemented in Mexico since February of 2012, just a couple of years after the UN agreement. The Mexican government enshrined the right to water access for all in its Constitution’s article 4 . As Gupta, Ahlers and Ahmed make the case, a human rights approach to designing and implementing human right to water legislation is appropriate, though tey recognize 3 types of bottlenecks (Gupta et al. 2011). In my view, the human right to water can be enforceable IF we have strong enough institutional and regulatory frameworks. As indicated by Olmos Giupponi, the HRW has elements of “justiciability” (Olmos Giupponi 2015). The mere notion of a human right should facilitate implementation and enforcement (both elements key to policy analysts and government officials). Nevertheless, we can’t just desire to implement the HRW as a policy directive but we also need to embed our thinking in a profound water ethic. That is, we need a place-specific, context specific strategy of water governance as posited by Schmidt and Peppard, where adaptive management takes place within a framework of a robust water ethic (Schmidt and Peppard 2014).

And thirdly, I still find it puzzling that much of the human right to water literature uses it as a frame of meaning and action is that it is separated from the human right to sanitation. I am often appalled by the treatment of sanitation in the global water governance discourse. For many, many scholars, activists and policy makers, the sanitation component of the water and sanitation Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) seems always relegated to being “the ugly duckling” in the equation. I find it puzzling that we are so concerned with the very idea of having a right to universal access to water while maintaining very little regard for the bodily functions that require most water (contrary to what many people may think, these are not food production!).

From a policy studies perspective, and to conclude, I would like to offer three concluding remarks.

First off, whereas previous conceptualizations of HRW focused on it as STRATEGY, I side with Mirosa and Harris (2012) in that we need to reconsider HRW as a framework for GOAL ATTAINMENT (Mirosa and Harris 2012). In public policy analysis, we focus and are much more interested in policy outcomes rather than strategic mobilizations. A proper implementation of the HRW will require us to use it as a framework that sets clear objectives for policy-makers and government officials rather than simply an emotionally-charged ideal goal.

Secondly, policy designs that aggressively push for public water supply should also engage with and bring along proposals to ensure global access to toilets, sewerage infrastructure and robust wastewater treatment (Pacheco-Vega 2015d). We can’t just focus on the human right to water, we need to ensure that we discuss the human right to sanitation. 2.4 billion people don’t have access to the dignity of a toilet, more than 950 million people defecate in the open. Think about it. We can’t have a human right to water that is disassociated from a human right to sanitation.

Thirdly, implementing the HRW will necessitate a focus on three simultaneous strategies: remunicipalization of private water service delivery, strengthening of local water utilities and regulation and control of the global bottled water industry across multiple scales. Not only will we need to ensure global access to publicly-supplied water, we will need to also make sure that private consortia are aware of the reasons why remunicipalization is occurring. Perhaps in finding the reasons why municipalities choose to de-privatize water utilities may lead to cooperative approaches to public service delivery (Furlong 2012) (what Furlong calls Alternative Delivery Models).

In closing, I would like to share one last thought that is specifically targeted to our student participants. As I have outlined in my talk, delivering the human right to water in a practical way is a tough challenge for governments and citizens alike, but if there is a reason I am a professor is because I strongly believe in the power of students to change the world. You can be that change. Every time you choose to consume water, remember that each bottle of water brings us one step closer to the global commodification of a human right. Don’t be part of that process. Thank you.

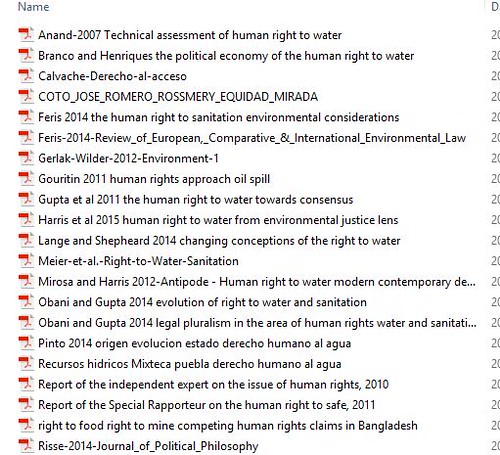

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bakker, Karen. 2007. “The ‘Commons’ Versus the ‘Commodity’: Anti-Privatization and the Human Right to Water in the Global South.” Antipode 39:430–55.

Furlong, Kathryn. 2012. “Good Water Governance without Good Urban Governance? Regulation, Service Delivery Models, and Local Government.” Environment and Planning A 44(11):2721–41. Retrieved January 26, 2014 (http://www.envplan.com/abstract.cgi?id=a44616).

Gerlak, Andrea K., and Margaret Wilder. 2012. “Exploring the Textured Landscape of Water Insecurity and the Human Right to Water.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 54(2):4–17.

Gupta, Joyeeta, Rhodante Ahlers, and Lawal Ahmed. 2011. “The Human Right to Water?: Moving Towards Consensus in a Fragmented World.” Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 19(3):294–306.

Hall, Ralph P., Barbara Van Koppen, and Emily Van Houweling. 2014. “The Human Right to Water: The Importance of Domestic and Productive Water Rights.” Science and Engineering Ethics 20(4):849–68. Retrieved (http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11948-013-9499-3).

Meier, Benjamin Mason et al. 2014. “Translating the Human Right to Water and Sanitation into Public Policy Reform.” Science and engineering ethics. Retrieved January 23, 2014 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24381084).

Mirosa, Oriol. 2012. “The Global Water Regime: Water’s Transformation from Right to Commodity in South Africa and Bolivia.” University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Mirosa, Oriol, and Leila M. Harris. 2012. “Human Right to Water: Contemporary Challenges and Contours of a Global Debate.” Antipode 44(3):932–49.

Olmos Giupponi, Belén. 2015. “Transnational Environmental Law and Grass-Root Initiatives: The Case of the Latin American Water Tribunal.” Transnational Environmental Law 1–30. Retrieved (http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S204710251500014X).

Pacheco-Vega, Raul. 2015a. “Agua Embotellada En México: De La Privatización Del Suministro a La Mercantilización de Los Recursos Hídricos.” Espiral: Estudios sobre Estado y Sociedad XXII(63):221–63.

Pacheco-Vega, Raul. 2015b. “Assessing ENGO Influence in North American Environmental Politics: The Double Grid Framework.” Pp. 373–89 in NAFTA and Sustainable Development The History, Experience, and Prospects for Reform, edited by Hoi Kong and Kinvin Wroth. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Pacheco-Vega, Raul. 2015c. “Transnational Environmental Activism in North America: Wielding Soft Power through Knowledge Sharing?” Review of Policy Research 32(1):146–62.

Pacheco-Vega, Raul. 2015d. “Urban Wastewater Governance in Latin America.” Pp. 102–8 in Water and Cities in Latin America: Challenges for Latin America, edited by Ismael Aguilar-Barajas, Jurgen Mahlknecht, Jonathan Kaledin, and Anton Earle. London, UK: Earthscan/Taylor and Francis.

Romano, Sarah T. 2012. “From Protest to Proposal: The Contentious Politics of the Nicaraguan Anti-Water Privatisation Social Movement.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 31(4):499–514. Retrieved (http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2012.00700.x).

Salman, Salman M. a. 2014. “The Human Right to Water and Sanitation: Is the Obligation Deliverable?” Water International 39(7):969–82. Retrieved (http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02508060.2015.986616).

Schmidt, Jeremy J. 2012. “Scarce or Insecure? The Right to Water and the Ethics of Global Water Governance.” Pp. 94–109 in The right to water: Politics, governance and social struggles, edited by Farhana Sultana and Alex Loftus. London, UK and New York, USA: Earthscan.

Schmidt, Jeremy J., and Christiana Z. Peppard. 2014. “Water Ethics on a Human-Dominated Planet: Rationality, Context and Values in Global Governance.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water n/a – n/a. Retrieved September 17, 2014 (http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/wat2.1043).

Sultana, Farhana, and Alexander J. Loftus, eds. 2012a. The Right to Water: Politics, Governance and Social Struggles. London and New York: Earthscan.

Sultana, Farhana, and Alexander J. Loftus. 2012b. “The Right to Water: Prospects and Possibilities.” Pp. 1–18 in The right to water: Politics, governance and social struggles, edited by Farhana Sultana and Alexander J. Loftus. London and New York: Earthscan.

November 19th marks World Toilet Day, perhaps the one day that justifies what has been the bulk of my scholarly research for the past 11 years. When you realize that World Toilet Day was founded in 2001 by Jack Sim, from the World Toilet Organization, and that it’s only been in the past three years or so that it has been adopted as a United Nations sanctioned official day (with UN Water as the official agency for WTD), you realize that the politics of global sanitation are much more complex than simply shining a light on the fact that more than a billion people still defecate in the open.

November 19th marks World Toilet Day, perhaps the one day that justifies what has been the bulk of my scholarly research for the past 11 years. When you realize that World Toilet Day was founded in 2001 by Jack Sim, from the World Toilet Organization, and that it’s only been in the past three years or so that it has been adopted as a United Nations sanctioned official day (with UN Water as the official agency for WTD), you realize that the politics of global sanitation are much more complex than simply shining a light on the fact that more than a billion people still defecate in the open.  I’ve also been extremely critical of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the post-2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in their “oh we’re totally going to change the world”, magic-pixie, fairy-dust, flying-unicorn version. Sanitation is the goal where the least progress has been done. Between 2.4 and 2.5 billion people don’t have access to the dignity of a toilet, and over 1 billion (a number that grew from 936 million) people still defecate in the open. Heck, in downtown Vancouver you can find open defecation because homeless people don’t have access to the dignity of a toilet! So, for me, the politics of sanitation governance are real because the big problems include lack of proper implementation mechanisms and political will to solve the issues.

I’ve also been extremely critical of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the post-2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in their “oh we’re totally going to change the world”, magic-pixie, fairy-dust, flying-unicorn version. Sanitation is the goal where the least progress has been done. Between 2.4 and 2.5 billion people don’t have access to the dignity of a toilet, and over 1 billion (a number that grew from 936 million) people still defecate in the open. Heck, in downtown Vancouver you can find open defecation because homeless people don’t have access to the dignity of a toilet! So, for me, the politics of sanitation governance are real because the big problems include lack of proper implementation mechanisms and political will to solve the issues.

Recent Comments