Anybody who reads my research blog and/or follows me on Twitter knows that I have very specific approaches to writing. Because I need a disciplined approach to life, I do things like the following: I schedule my life to the every minute, I organize my office every day, I organize my research notes and books/journal articles almost obsessively. Writing every day has become my mantra and my daily discipline.

Anybody who reads my research blog and/or follows me on Twitter knows that I have very specific approaches to writing. Because I need a disciplined approach to life, I do things like the following: I schedule my life to the every minute, I organize my office every day, I organize my research notes and books/journal articles almost obsessively. Writing every day has become my mantra and my daily discipline.

Because I need the peace of mind of having accomplished something every day, I write every day, instead of spending extended periods of time cranking out text. I write every day because I’ve made writing my priority. Everything can wait but not writing. I can’t leave my house without doing some writing.

Every single researcher (and writer) out there will provide the advice that works best for him or her. A recent piece on Inside Higher Education(which I loved by the way, because she’s such a great writer) by Dr. Jane Ward suggests that you should “write in sprees” (e.g. write for extended periods of time), instead of writing every day. She also suggests (which I find is one of the most powerful piece of advice anybody can give) to self-identify as a writer.

Every single researcher (and writer) out there will provide the advice that works best for him or her. A recent piece on Inside Higher Education(which I loved by the way, because she’s such a great writer) by Dr. Jane Ward suggests that you should “write in sprees” (e.g. write for extended periods of time), instead of writing every day. She also suggests (which I find is one of the most powerful piece of advice anybody can give) to self-identify as a writer.

This is something I do (identify myself as a writer), because in a former life, I wrote PR and marketing copy. Ask me one day over cocktails. Her third piece of advice is also extremely powerful: don’t absorb other people’s anxieties. If somebody else is stressed, don’t let that stress get you down.

But I want to go back to the first piece of advice, because that’s the one I find most people struggle with – should you write every day or should you write in long sprees. Inspired by Dr. Wendy Laura Belcher (whose 12 weeks to a journal article book is an absolute gem that you should buy this very second, and whose writing advice is stellar), I went on Twitter to rant about this notion of “don’t write every day”.

The truth is: YOU ARE WRITING EVERY SINGLE DAY. Even if you are sending emails to a coauthor about how to craft a specific section, THAT COUNTS AS WRITING. Why? Because you are sharing concept notes. You are shaping how your argument is going to be structured. You are discussing the data. Are you reading and taking notes off of each paper you read? You are WRITING.

The truth is: YOU ARE WRITING EVERY SINGLE DAY. Even if you are sending emails to a coauthor about how to craft a specific section, THAT COUNTS AS WRITING. Why? Because you are sharing concept notes. You are shaping how your argument is going to be structured. You are discussing the data. Are you reading and taking notes off of each paper you read? You are WRITING.

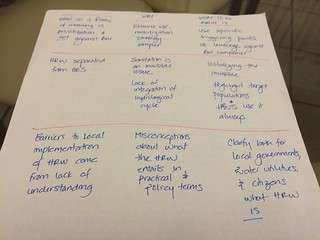

Are you drawing tables by hand to decide how you’re going to present them in your paper? YOU ARE WRITING. You are, in fact, WRITING.

Most people who write about academic writing (now that’s writing-ception) will differentiate between “generative text” (words you will end up putting into a paper or grant proposal) and “non-generative text” (bits and pieces of writing here and there). In reality, even if you don’t structure full sentences or write a full paragraph, every time you write something that pushes your work forward, you ARE writing, and you ARE writing “generative text”.

One of the problems I have found with recently published papers (and this may be the result of our publish-or-perish attitude) is that their literature reviews are exceedingly poor. Sometimes I find that key citations are absent from papers whose authors should know better. I believe one reason for this is that we don’t take the time to read and write notes about what we read. And we don’t because, WE SHOULD BE WRITING. If we don’t take reading seriously, if we don’t write notes and assemble robust literature reviews, our writing will end up being quite poor.

Our obsession with producing generative text has also led us, I believe, to relegate reflection to a distant second place. We don’t make time for proper reflection and digestion of ideas and thoughts on an every day basis. What is important in my daily academic practice? WRITE. WRITING. I NEED TO BE WRITING. But we don’t make the time to reflect. And the notes you write to yourself while you read and reflect on ideas? THAT COUNTS AS WRITING. That IS, in fact, writing.

I think we owe it to ourselves to recognize that no writing practice is perfect, or ideal, or that every single piece of advice you receive will work for you. You need to build your own writing practice. But to do so, you also need to recognize that many of the activities you don’t reward yourself for doing (like writing notes by hand, like emailing colleagues with ideas and thoughts, like reading, reflecting and taking notes about what you read) are in fact, whether you recognize it or not, writing.

My Twitter rant below:

Forgive me, but I'm about to send out a rant of about 6-7 tweets on #AcWri practices. Bear with me for a few.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Every day you write on your laboratory notebook, you exchange emails with collaborators about how to go about a specific project, you #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Every day you read a journal article, a book chapter, bits and pieces of a literature review for a grant proposal, you're #AcWri-ing.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Every day you draft ideas on paper, you add a Post-It note with thoughts about a specific article, you write on your whiteboard, you #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

So, for everyone who tells me "I don't like your #AcWri practice of writing every day", you ARE in fact, writing EVERY SINGLE DAY.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Producing conference paper, journal article, book chapter, book manuscript text that you can then edit and send into the world, is #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

But to build a writing practice, you don't necessarily need to write "generative text" every day. You could just be writing notes! #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

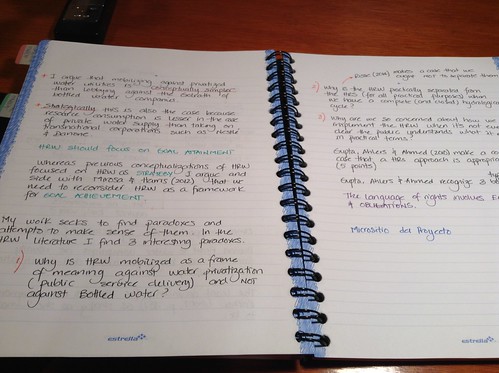

I wrote my #ISA2016 paper in ONE DAY. That, to many people, is considered "binge-writing". But I had PLENTY of handwritten notes already.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Let's dispel once and for all with this fiction that you are not #AcWri-ng every day. You ARE EXACTLY #AcWri-ing every single day.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Right now, because I'm so behind with my #AcWri I'm experimenting with #AuntieAcid's approach -> pic.twitter.com/lb7rVg1hJB

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

You CAN build a "write X number of hours of generative text" every day, or you can "write for 4 days, then pass out". It's YOUR #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

I strongly believe we need to change how we see this. You wrote, for stuff you then will at some point publish 🙂 https://t.co/0jEvofwCml

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

We need to add value to the so-called "preparation" and register it as "writing" and validate it. https://t.co/1sAn1m0A5a

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Much of my own #AcWri advice mirrors people whom I respect a lot: @WendyLBelcher @tanyaboza @JoVanEvery @ThomsonPat @explorstyle

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

I respect that people may need to do what I'm doing this week: sitting at my desk and cranking out papers like there's no tomorrow. #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

But I have FIVE (yes, FIVE) conference papers to submit, plus two book chapters. and I was ill for five weeks. So I need to crank out.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

That doesn't mean I won't continue my daily, two-hours of #AcWri practice. It means I will EXTEND the number of hours I am writing.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

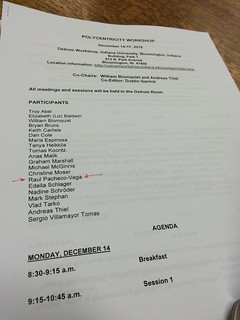

I KNEW I needed to publish HIGH, and a lot of papers. So I signed up for #ISA2016 #MPSA2016 #WPSA2016 #LASA2016 #CPSA2016 #PMRC2016

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

All conferences I signed up for, require you to write full-fledged papers, which I then will submit to a journal. I FORCE myself to #AcWri

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

Sorry, that was my early morning #AcWri "do what works best for you" rant. I do hope it helps you rethink your own practices.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 11, 2016

UPDATE: Dr. Melissa Terras suggested a change in the wording of “binge-writing” that will shape how I write about this topic in the future. As Katrina Firth aptly suggested, the word “binge” suggests some sort of abnormalcy. We usually associate binging with “binge eating” or “binge drinking”, both of which may lead to physical illness.

@WendyLBelcher @JoVanEvery @raulpacheco @explorstyle @ThomsonPat I hate the term binging–it suggests sickness. I get lovely flow & yes +

— Katherine Firth (@katrinafee) August 2, 2015

Melissa Terras suggests “writing sprints” instead of “binge writing”, and I love this idea.

@raulpacheco loved the piece. Just to say – some folks use “writing sprints” rather than “writing binge”, may be useful!

— melissa terras (@melissaterras) March 13, 2016

Jo Van Every had already written about the use of “binge writiing” and I didn’t recall until I searched for associated tweets. I also thoroughly agree with Professor Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch that if you want to sprint, you can’t do it unless you’ve trained daily, which is the theme of this post (how every writing you do can actually count as #AcWri).

YES to writing sprints! And you cannot sprint if you have not regularly trained #acwri https://t.co/SBTts0SFj8

— MHH (@MHoussayH) March 13, 2016

FURTHER EDITS: Wendy Laura Belcher and Jane Ward had a dialogue in the comments on the Inside Higher Education piece, and also with me.

@WendyLBelcher @raulpacheco me too. in the dialog with Wendy, i distinguish between "writing process" activities and "dedicated writing."

— Jane Ward (@thequeerjane) March 13, 2016

Furthermore here are a couple of additional thoughts by Pat Thomson who also has written on this (I’m changing my vocabulary as shown to “sprint writing” or “writing in long sprees”).

@raulpacheco @WendyLBelcher @katrinafee @melissaterras it's about suiting time to task I think. Multiple tasks, multiple #acwri methods….

— pat thomson (@ThomsonPat) March 13, 2016

@raulpacheco @katrinafee Yes, I'm also removing binge from my vocabulary. It's not the right metaphor. I'm using "marathon-method writers"

— Wendy Laura Belcher (@WendyLBelcher) March 13, 2016

@raulpacheco @WendyLBelcher @melissaterras Love 'sprints'. As a long distance runner and writer, sprinting & running resonates too.

— Katherine Firth (@katrinafee) March 13, 2016

And the book recommended to me is one I already own in PDF version. “How We Write” edited by Suzanne Conklin Akbari. Great read.

Recent Comments