It’s been an excellent few months for me, because I have been able to share more of my “tricks and tools of the trade” with people who read my blog, and readers seem to like how my workflow processes help them with their own. As always, I don’t provide “advice”. I simply share my experiences in hopes they will help other academics who are at similar stages of my life, or my own students (or other professors’ students!).

An 'everything notebook' works for me. It's worth a try! https://t.co/C79l7w5FYt

— J Burisek (@DocJLB) August 25, 2016

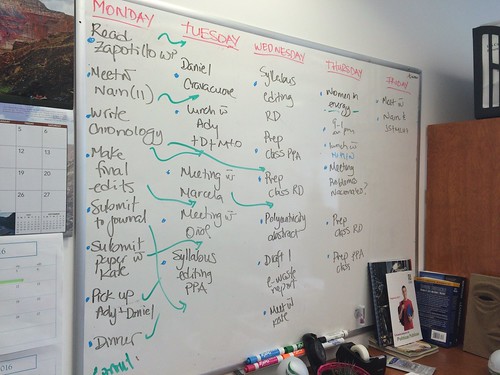

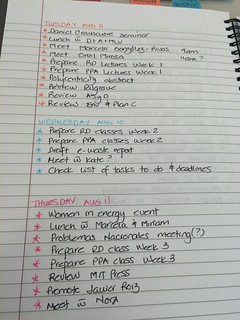

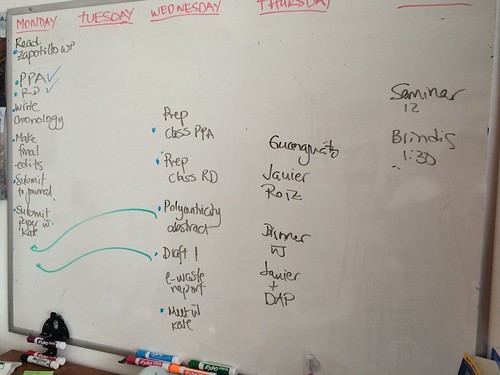

One idea that came to me recently is that, while folks seem excited with the concept of the Everything Notebook (to keep track of their To-Do lists, research notes, ideas, etc.) I don’t think I wrote what I believe are the key elements of how the Everything Notebook works from the start up. In my view, the two things that make my Everything Notebook work for me are the durable plastic tabs and the use of colour (in my case, Sharpie 0.4mm fine markers, and multiple colour highlighters). The third element is the flexibility and ease of adjustment of an Everything Notebook. I can move stuff around very easily, as shown below.

This is what I bring everywhere (not pictured here: my Everything Notebook) pic.twitter.com/XRNS0BQE2x

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 5, 2016

The key to the Everything Notebook’s simplicity is that you don’t need to create an Index (as opposed to the Bullet Journal). Because the Everything Notebook has descriptive titles in each of the rigid plastic tabs that are attached to each section, you don’t need to have a detailed index. While I do try to save some pages for Research, a few for Students, space for To Do lists, and a few pages for Administrative Tasks, I don’t fret if one thing runs over another, or if I end up having to move the plastic tabs from one page to another. The beauty of using plastic durable tabs is that they’re mobile. You don’t depend on specific dividers and therefore, you can vary how many pages you use for each section.

This is my "Everything" Notebook. Each component (meetings, notes from seminars, fieldwork notes) has plastic marker pic.twitter.com/9uSejXeRJh

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 1, 2016

Another important element is flexibility of notes’ location. Because I label each page or set of pages with a cue to the specific content that is in that page, I don’t necessarily need to write all my To Do lists in a specific location. All I do, particularly if I run out of space, is tag the page with the proper cue so that I can know what exactly is filed where.

At the Mexican water law national meetings – for those wondering, yes, at meetings I do use my Everything Notebook. pic.twitter.com/RByi0RZrTj

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 4, 2016

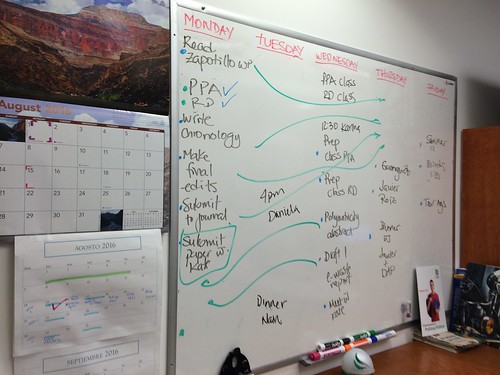

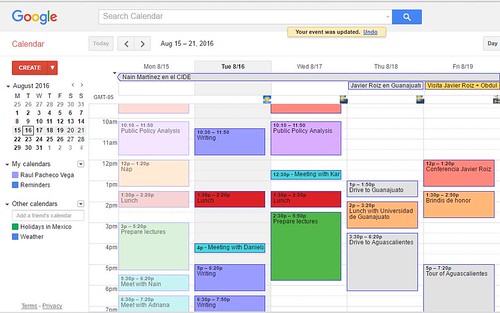

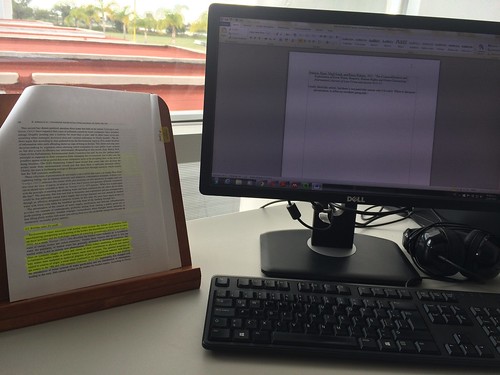

As shown above, I bring my Everything Notebook everywhere. Even if I’m working online (writing notes, or editing papers), I keep an analog medium to jot down ideas and/or To-Do items. My Everything Notebook is always synchronized with my Project Whiteboard and Google Calendar. I’m also glad other people have taken up the concept!

@ReadingRachelb My planner notebook has become my everything notebook and I love it! https://t.co/0dobkcIj6s

— Brit Paris (@brit_paris) July 7, 2016

The important thing for me is that the Everything Notebook gives me the flexibility of not having to be strict about content, or location of said content. I can have a To Do list, followed by a few notes from a scholarly seminar, followed by ideas about a research project, followed by notes from my lectures or scribbles related to a new research paper. Because I use the plastic tabs to organize the notebook, I always know exactly what is located where.

Sometimes people don't believe me when I say I actually only use one, Everything Notebook. Here is proof. pic.twitter.com/8M2d43I56W

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2016

And more importantly, I use the Everything Notebook everyday. I carry it everywhere. My students, colleagues, other academics, participants in meetings, people whom I’ve interviewed during fieldwork, everyone has seen the Everything Notebook, and so far everybody has understood what I use it for.

Caveats to using an Everything Notebook

There are obviously a couple of caveats, though. The first one is obvious, some people are colour-blind and therefore using colour will not help them. The advantage of using plastic tabs (and you can even use traditional adhesive mini-notes) is that you don’t depend on a colour-code. You can simply turn your Everything Notebook around and read what the tab says.

The second caveat is obviously that you need to carry the Everything Notebook around. I do, and it’s the first thing that I usually bring with me. Except when I don’t, and then my life is completely screwed up. That’s why it’s important to have the meetings synchronized with Google Calendar (because my iCal is synchronized to my Google Calendar, so I may forget what I’m meant to be doing, but I don’t miss where I am supposed to be or which meeting I should be attending).

The third caveat is that you may run out of space. If so, and it’s happened to me before, you can start a new Everything Notebook. Just keep the previous one handy in case you need to confer. I have my two most recent Everything Notebooks at my office at the ready just in case I need to confer about specific datasets, ideas, fieldwork, etc.

The Everything Notebook in action, beyond writing and To-Do list planning.

When discussing how to operate the Everything Notebook, Dr. Veronica Kitchen from University of Waterloo asked me what would we do if there are some notes you took by hand in your Everything Notebook and you don’t remember where you left them.

@raulpacheco @amandabittner @A_M_Collins what do you guys do with notes from stuff you've read over time? I like to take them by hand, 1/2

— Veronica Kitchen (@vmkitchen) August 25, 2016

@raulpacheco @amandabittner @A_M_Collins but tend to lose track of what notebook they are in (& what I took notes on vs. Just skimmed)

— Veronica Kitchen (@vmkitchen) August 25, 2016

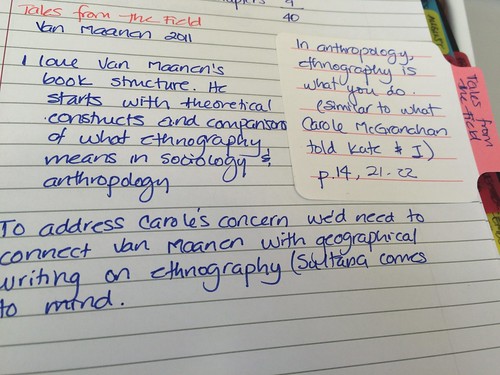

As I noted below, when the article or book chapter, or book, or report is worth writing a memo about (or memo-ing), then I insert a larger tab where I write the citation.

@amandabittner @vmkitchen @A_M_Collins to recognize paper worth memo-ing in EvNoteBk, I use longer tab (see here) pic.twitter.com/2ICfbBGa7W

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 25, 2016

When people ask me “how do you find stuff in your Everything Notebook”, I show them how I use plastic tabs (they’re pretty sturdy and rigid) to mark the content. I use very descriptive titles so that I can find quickly. Also, I use the tabs on the right hand side, on the top and on the bottom.

@amandabittner @vmkitchen @A_M_Collins I use very descriptive tabs so I can quickly find stuff at a glance pic.twitter.com/2jHQ8LY5ip

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 25, 2016

From the example below: “Lucero Radonic” means notes from my Skype meetings with Dr. Lucero Radonic from Michigan State University, a water anthropologist who shares interest in water governance in Mexico with me. “Seminar with Debora” refers to a seminar I attended that Dr. Debora VanNijnatten (a good friend and colleague from Wilfrid Laurier University) gave at CIDE earlier this year. “LASA 2016” are my notes from the panel where I presented at LASA in late May of this year. “Goals June 2016” should be obvious, those are my writing and mentoring and teaching goals for June.

It is also clear that sometimes you scribble things in notepads, or Post-It notes. You don’t want to lose those notes, and you wonder how to integrate them to the Everything Notebook. What I do is: I staple them. That way, I know for a fact that I won’t be losing the notes I already had written for a project, or a To-Do list that I ended up drafting on a plane or in a line to enter a building.

@amandabittner @vmkitchen @A_M_Collins if I write in loose pages, staple to Everything Notebook, add filing tab pic.twitter.com/BfQYNIt3Ud

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 25, 2016

I am just happy to see that people find my methods useful. Hopefully this post will help those who may need an organization system that doesn’t have to be perfect (because I am FAR from perfect myself!)

Recent Comments