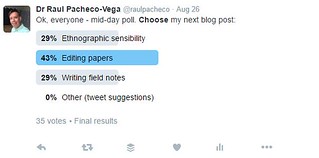

When looking at my publication record, many people have told me that they were amazed that I had published so much in such short period of time. While I am positively flattered that they think so, I don’t consider myself a particularly productive academic. Yes, I’ve published a lot in the past few years, the result of a focus-on-quantity strategy designed to be awarded Level 1 of the National Researchers’ System (Sistema Nacional de Investigadores, SNI) of the Mexican National Science and Technology Council Research (CONACYT, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, the Mexican equivalent to the NSF in the US or the Tri-Council in Canada).

For my institution, being recognized as a National Researcher is a distinction that is important and therefore, I wanted to comply with this requirement. While not an explicit request from my institution, it’s something that is expected, that CIDE professors will be members of SNI. This doesn’t mean that I published stuff of lesser quality, it means that I did basically nothing else but research and write for the vast majority of the past four years. As a result, many of the pieces I had under review came out during that period, making it look as though I was a researching writing and publishing machine. This isn’t really the case.

Like many other scholars, my strategic choice in order to have a well-populated publication pipeline is to have several projects on the go. Juggling different projects IS a hard balance. Do I want to narrowly focus on just working on one strand of a broader research agenda? Or do I want to expand my portfolio and work on several different issues/topics/methods? Personally, I have chosen the latter because that is what makes me feel more fulfilled. But the truth is that every single project I undertake takes time.

Like many other scholars, my strategic choice in order to have a well-populated publication pipeline is to have several projects on the go. Juggling different projects IS a hard balance. Do I want to narrowly focus on just working on one strand of a broader research agenda? Or do I want to expand my portfolio and work on several different issues/topics/methods? Personally, I have chosen the latter because that is what makes me feel more fulfilled. But the truth is that every single project I undertake takes time.

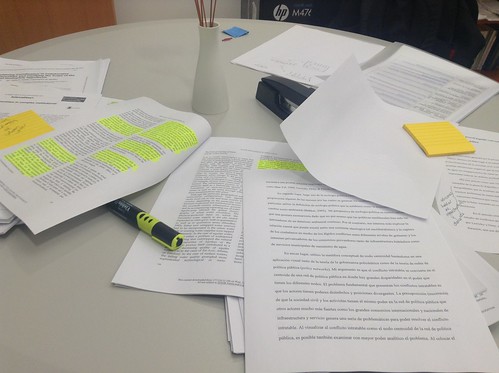

As I have posited before on Twitter, you can’t rush good research. And you need to put in the work. You can’t just skip to the part where you are already awesome. Gaining new insights, building datasets, inputting citations into your reference manager, reading papers, summarizing data, coding the mathematical and statistical models that you are going to run, going into the field, writing field notes, assembling projects, writing grants, preparing lectures, writing lecture slide decks, all of this means DOING THE WORK. You can’t rush any of this. You need to put in the hours, and do the work.

Overnight success takes anywhere from 10 to 15 years, and WORK. You can't skip to the part where you're awesome. (comic via @savagechickens) pic.twitter.com/SIqo09V6hC

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 4, 2016

One of the best papers I have written, a paper that I coauthored with my good friend and colleague Dr. Kate Parizeau (University of Guelph), has taken almost a year to see it from original idea to fruition. My work on the politics of sanitation and wastewater governance started in 2004. Twelve years. I have studied the coalition-building and influence-seeking strategies of transnational environmental non-governmental organizations since the year 2000. SIXTEEN YEARS. Good research takes time.

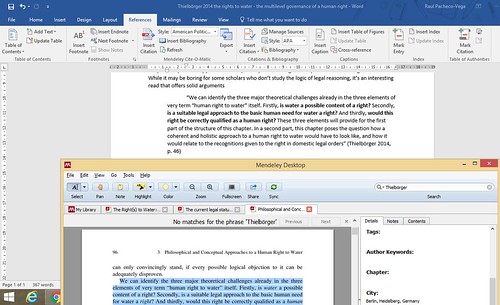

All y'all: I've been writing and researching since 7:00am. It's almost 1pm. I have written 600 words, and a table pic.twitter.com/3z4FW2yDtc

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 8, 2016

The truth is, scholarly work involves NUMEROUS TASKS.

This morning I had to free-write, research, assemble a table, write 2 memorandums, pull quotations, clip articles into Evernote, Mendeley.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 8, 2016

And one of the least valued, unfortunately, is reflection. We need time, often long hours, to reflect, read, consider thoughts, ideas and marinate what we want to say. Yet we are deeply embedded in a culture that demands more from academics (students and professors alike). Thus what we end up getting is overworked professors who don’t have the time to reflect (and thus may actually produce work that is of less quality than they could if they had the time to read, think, ponder).

Doing research, especially GOOD research, requires time investment, focus, concentration and can't be "sped up". Thus #SlowScholarship

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 8, 2016

I am a fan of slow scholarship, despite the fact that I do many things fast (touch-type 100wpm, and speed-read). At the same time, I am well aware of the fact that producing good research will take me A LONG TIME. Even without taking into account the sometimes extremely long time that it takes for journals to provide a peer review report, let alone publish our journal articles.

I’m not even sure this blog post has a major central point, but I just wanted to emphasize that doing good research takes time. Taking the time to reflect and refine our thinking is a major component, and it worries me when I see some PhD programmes that take 3 years, because it is clear to me that those PhD students have not been given the time to really marinate, ruminate and process the literature. I really think we need new models of thinking about academic work that champion less “publish-or-perish” and more “publish the best work you can produce”.

Recent Comments