Recently, my good friend Dr. Amanda Bittner (Memorial University of Newfoundland) told me that she was suffering from focusing again a lot on teaching and as a result, her research was not progressing as much as she would have wanted to.

My biggest fear has always been not being able to publish (or not sustaining my daily writing practice) throughout my heavy-teaching semesters. I do acknowledge again my privilege: the most I teach per semester is two courses (both of them usually undergraduate level, which take a lot more preparation than graduate-level seminars). I usually teach two courses in the fall, which means that I also need to schedule a lot less travel. Unfortunately, many of the things I do require me to travel for fieldwork or to do project-related work. I was in Berkeley (California) a couple of weeks ago finishing my e-waste governance project, and I need to travel to New Haven for the EGAP18 workshop. Therefore I always need to strategize how I am going to sustain my research during the heavy-teaching semester.

Here are a few things I do, and again I acknowledge my privilege in that I get some perks by being organized.

1. I teach only Mondays and Wednesdays.

I request this time slot for several reasons. First, it allows me to do fieldwork or travel for my research during Thursday and Friday. Second, it also gives me leeway to do service-related work. The first three days of the week NEED to be focused on teaching (although I usually prepare lectures on Friday, because I am distanced enough from the two days of teaching that I feel fresh and know exactly what I plan to do for the following week.

2. I schedule full days for research.

It’s rare that I will allow service to creep into my research days. Usually I focus on teaching and service during Mondays and Wednesdays. This is the result of many years of practice. I know for a fact that I finish my lectures exhausted. But I can easily find reviewers for a journal article, or input references into Mendeley, or answer emails related to faculty or student stuff. I can also grade on days that I’m teaching, because I usually take a nap and feel refreshed. So I can come back to grade without having to devote entire days to it.

3. I schedule a buffer day.

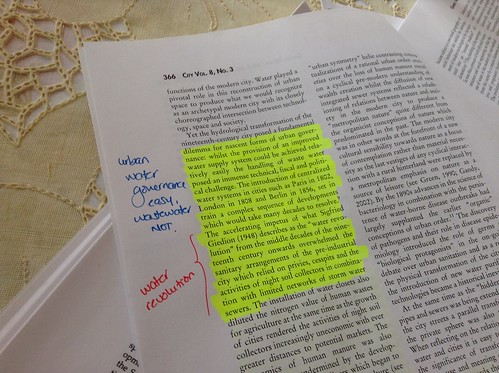

My buffer day is usually focused on catching up on research and reading. This means that during that day, I’m not allowed to have meetings, I’m not allowed to answer service-related emails, I’m not allowed to think about the next lecture. All I do during the buffer day is research and read. You may think “how is this different from having a research day?” Well, during a normal research day, I know that there are things that need to be done regardless of the fact that I am doing research. I must meet with a student, I must read a graduate student’s thesis. But during my buffer day, I catch up on stuff that I would leave behind if I didn’t have that day. For example, if I am finishing a paper, I schedule all my reading for said paper for Thursdays. I know for a fact that I may need to schedule meetings on a Tuesday, or a Friday. But on Thursdays, no meetings whatsoever. Maybe I should call my buffer day my BLOCKED day.

4. I focus on my physical health first.

I try hard to sustain my exercise in the morning regime, I pursue good eating habits. I know for a fact that I can fall ill during a teaching semester (after all, this has happened to me 3 years in a row). So during heavy-teaching semesters, I make even more of a point to rest and take care of myself.

5. I front-load my lecture slide deck preparation

Because I know that I still want to do research, yet I want to be an excellent teacher, I front-load my courses’ preparation. I usually spend a couple of weeks before the semester starts preparing lecture slides for the next 2-3 weeks. And since this year I started teaching again public policy theory courses (which I already had done at UBC), I feel much more at ease when I am lecturing because that’s material I know really well.

6. I take weekends off (mostly)

I say mostly because given that I spend my weekends at my Mom’s house, and I have a full-fledged home office in my bedroom, it’s inevitable that I’ll wake up early and do *some* work. But I usually read during weekends, which also allows me to catch up on work. But more importantly, I spend the weekend with my parents, my brother (when he visits), my friends. And napping. Lots of naps.

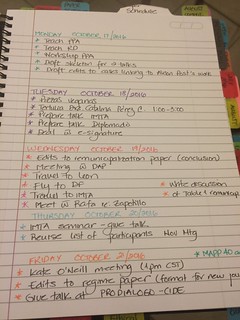

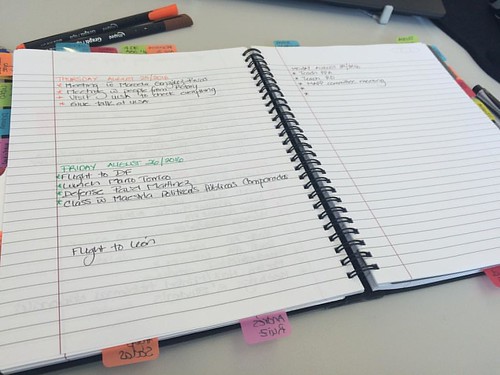

7. I plan my week on Sunday nights.

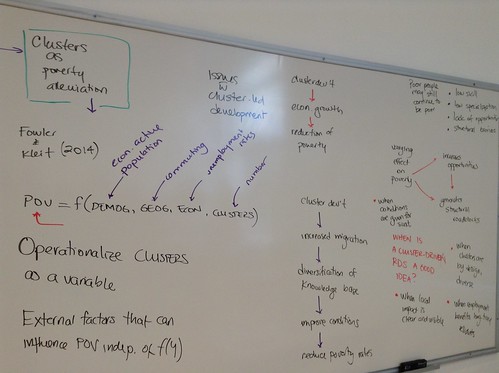

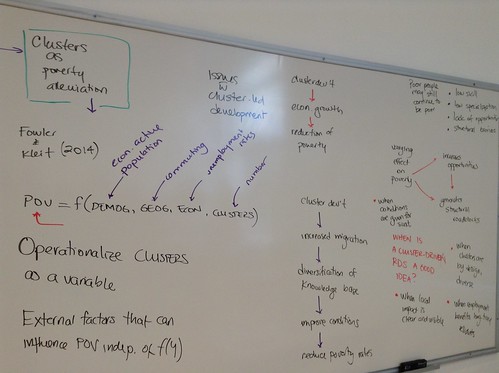

I am a bit of a Type A. I need to have a relatively rigid schedule, a daily/weekly plan, a monthly strategic plan, and a publications plan. So I spend about 20 minutes every Sunday night planning exactly what I am going to be doing the following week. I also coordinate my weekly plan with my Project Whiteboard so I know all my projects are moving forward. But then I sleep well on Sundays because I know which pieces of research need to be done by when.

These strategies aren’t applicable to everyone, I know, but these are things I do that I am sure can be adapted in other environments.

Recent Comments