Given my field of research (the governance of non-traditional common pool resources), it’s often easy to write about the negative effects of lack of access to water and sanitation can have on women. For previous International Women’s Days, I’ve written about the disproportionately negative impact that open defecation and lack of menstrual hygiene management strategies can have on women and girls, including the very real threat of sexual violence. I also have written about how women often share the biggest burden of home-based work and informal work, specifically in waste picking (which is the activity I’ve studied).

An estimated 384 million women and girls are without safe water. https://t.co/FMJmNb8aFG #InternationalWomensDay #IWD2016

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 8, 2016

But this year, I wanted to write about a different topic. I think it is important that we reflect on the fact that women still face structural barriers to their development in academia. This is not something I am making up, it is something I have witnessed since my childhood, and now as a professor I am even more keenly aware of it. I have heard horror stories of hiring committees where female candidates have been asked about prospects for children-bearing, and for getting married. At a few conferences, I have heard snarky comments on whether female students and/or professors are quantitative enough (or how their only trick is doing statistical analysis). I have been asked (seriously) why do I push so much for the inclusion of female scholars’ writing in syllabi, not only in mine (where I can proudly boast I have 67% of female scholars’ works), but in other professors’ too.

My lab is 60% women. About 60% of my coauthors are women. My courses on pilot analysis and economic geography have 67% women's readings.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 8, 2017

I am the son of a professor of political science. My Mom faced structural challenges to career development, even when she decided to do her PhD (apparently, she was too old to do it in France, so she decided to go to one of the best schools in Europe for political science, the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she was welcomed with open arms). I am the uncle of a political science and international relations major (who, by the way, studied with some of the most awesome political scientists at University of Pittsburgh, who also happen to be good friends of mine). So whenever I hear the notion that “not everything is about gender”, I cringe.

With my favourite political scientist, Dr. Obdulia Vega (aka my Mom). pic.twitter.com/Wraotg7UhS

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 9, 2016

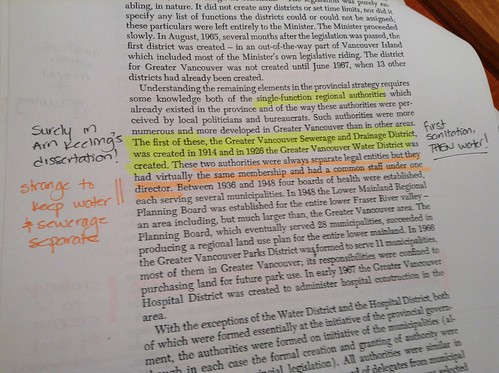

Honestly, everyone should push for gender equality in academia even if their Moms or nieces aren’t political scientists. But apparently this is a topic that is still hotly debated, because some people seem to think that women haven’t faced structural barriers (the so-called glass ceiling). Even though there’s serious scholarship on how female scholars are cited less than their male counterparts, how their work isn’t used as often in syllabi as male scholars, how stopping the tenure clock for parental leave benefits male academics more than female ones. This frustrates me to no end.

But in closing on a positive note, I wanted to celebrate the women in my life, especially those scholars who help me learn and grow every day, those students and research assistants of mine who keep pushing me to be a better scholar every day as well. As far as the day goes, International Women’s Day doesn’t feel as much a celebration but more as a recognition of the fact that we have come a long way, but we still have a lot more to go.

Recent Comments