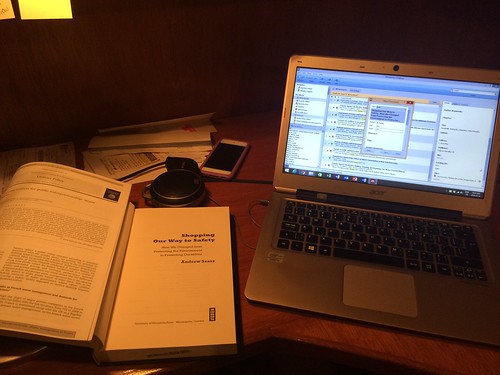

The second book in my list of volumes I’ve been reading which focus on academic writing is “Stylish Academic Writing” by Helen Sword. She has a series of three books, of which I had bought two, the first one being Stylish Academic Writing. A lot of people had recommended this book, on Twitter, when I first started doing Twitter threads on books on academic writing.

Trust me when I say that my credit card will be suffering for a long while, because I went on a shopping spree for writing academic articles’ books. I had already read Patricia Goodson’s “Becoming an Academic Writer” and Graf and Birkenstein’s “They Say/I Say“, which I use in my writing policy lab.

I'm in love w/ Helen Sword & her writing. She did an actual study (scholarly, systematic research study) on what constitutes stylish #AcWri pic.twitter.com/T7qykTVZ63

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

I think I got excited about doing these threads because people responded so well to my previous one on Patricia Goodson’s “Becoming an Academic Writer”.

I had previously written about William Zinsser’s book, “On Writing Well”. Sword’s book is very different from Zinsser, not only in tone and focus, but also on the actual premise. Sword did an actual, rigorous, scientific study of stylish academic writers. Like Zinsser, Sword argues (quite correctly) that nobody teaches us how to write academic prose. We are sort of expected to imitate our PhD advisor, I suppose?

Sword is entirely right: nobody teaches you (during studies) how to #AcWri. Like teaching it's one of those skills you're expected to learn pic.twitter.com/ZgFDBeEwir

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

Sword finds 6 recommendations where her interviewees offer inconsistent recommendations. I have my opinions on all of them. YES to all. pic.twitter.com/Zkr14xzSlR

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

Helen Sword, in Stylish Academic Writing, recommends the use of the active voice (“I”). I am a big fan of this mode of writing. I find the passive voice to be an oversimplified model of how we should be writing for a particular target audience. I also find it pseudo-scientific.

Hell, one of the best articles I've read in Econometrica (Melissa Dell's study of Mexican drug trafficking organizations) she writes as "I".

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

One of the things that has become really hard for me to teach my students is how to find the key (foundational) sentence in a paragraph. Most writing courses will encourage you to have it at the very beginning of the sentence. Many academic authors don’t do it, unfortunately.

In her writing, Helen Sword demonstrates the importance of a key sentence that encapsulates the main idea of the paragraph. 3 examples: pic.twitter.com/Z3eFORTjgi

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

One of the things I found most useful was the “Creating A Research Space” (CARS), or what Zinsser and others call, “the hook”. Why exactly did you do the research you conducted?

Note that here's where Graf and Birkenstein and Zinsser and Sword all converge: what's "the hook" of your paper? How does it contribute? pic.twitter.com/5fE71WtuLR

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

What's the story your data, your regressions, your archival research, your novel tells us? My PhD advisor said "research is storytelling"

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

Human geographers and sociologists in love with Foucault: Sword says that your absurdly convoluted #AcWri is not justified by Foucault: pic.twitter.com/fBa4NakvB6

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

I am a fan of storytelling. I teach my students that “research is stories you share based on rigorous data analysis and robust theoretical grounding” (a very similar model to what I was taught by my PhD supervisor). I’ll confess that I was very disappointed by the little coverage that Sword devoted to Storytelling.

I disagreed with Sword on the politics of citation, and I also had a few minor quibbles here and there, but overall, I loved the book, and I would recommend it to anybody who is interested in academic writing.

Verdict: another solid book, which is worth a read. I'd probably come back to several chapters by Sword on an end-of-term reading spree.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 24, 2017

Recent Comments