Even though I travel just about every week, I’m never very good at determining how many articles I can realistically read, or how many words I will be able to write. But I always use a time-based approach to my research. How much work can I do in the next hour? The next 30 minutes? The next 2 hours?

So, for example, when I first started writing this blog post I was sitting at the Atlanta Jackson-Hartfield airport on my way to Waterville, and I knew I had about 15 minutes until we had to start boarding our plane headed to Portland (Maine). I knew I could crank a blog post in less than 15 if I already knew what I’m going to say. I wrote a first draft of this blog post, published it and then realized that it wasn’t nearly complete enough.

So now that I’m on my way to Vancouver and sitting at the Mexico City airport waiting for my next flight, I’m editing this blog post. While blogging doesn’t technically count as #AcWri, I am using it to remind me of the things I need to write this next week. It also does help when I can write on the plane.

Having both seats available and lots of legroom in my flight to Atlanta allowed me to do a lot of #AcWri pic.twitter.com/gLocwyGyUy

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 6, 2017

Let me give you another example of a time-based approach to working – the other night, I accompanied my Mom to a meeting. I drove and brought along enough work to keep me busy for about an hour, or 90 minutes. I figured I could skim an edited volume and write a couple of rows in my Conceptual Synthesis Excel dump. I did manage quite well.

Note how each chapter of the book is a row in my Conceptual Synthesis Excel dump – also note I chose Ch 5 as it looks more theoretical pic.twitter.com/hBli6oc1qG

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 5, 2017

I managed to write text for a few entries in a two of my Conceptual Synthesis Excel dumps: the Bogartz et al 2016 sanitation for all edited volume and five articles on the anthropology of human waste.

In summary, I started and almost completed 2 rows of 2 Excel dumps (total 4), skimmed 2 book chapters, wrote 255 words of a memorandum.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 5, 2017

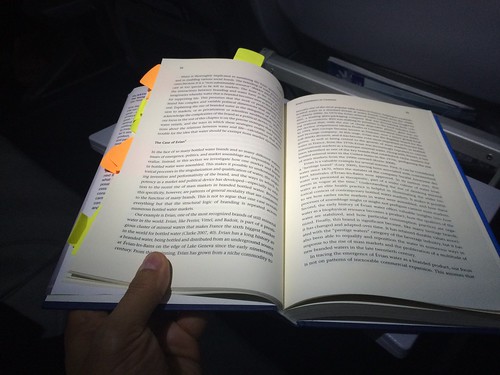

On the Aguascalientes-Atlanta flight, I managed to finish reading the Walsh 2015 article, and write a 420 memorandum on the topic. It was a 3.5 hour flight, and I still managed to get a nap in. Then on the Atlanta-Portland, I managed to finish highlighting and reading and scribbling on the margins of the Kaplan 2007 article.

I used text I wrote on live-tweeted annotations of Molotch and Borén's edited volume toilet to write components of a memo and a row in Excel pic.twitter.com/486Av5BDpo

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) November 4, 2017

I think the basic rule for me is bring enough work to write at least two or three memoranda (that means, 2-3 journal articles) and the equivalent of one book’s worth of Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump row entries. In total, that’s about 8-10 pieces of reading if you count 5-7 book chapters per book.

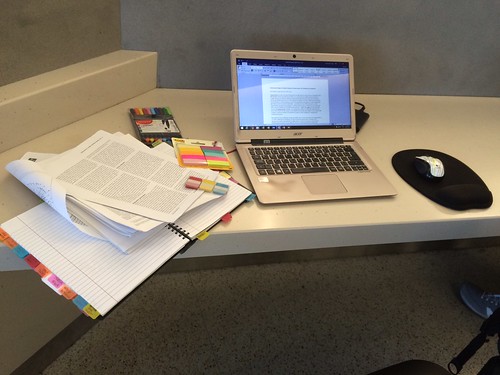

For example, for this Vancouver trip, I brought along 13 journal articles. 7 of those I’ve already highlighted completely, so I can just add my scribbles to an Excel dump (7 row entries). The Mexico City – Vancouver flight is 6 hours long. I can devote 2 to a nap, 2 to highlighting and reading, and 2 to writing. And once I land in Vancouver, I’ll spend some time adjusting my writing schedule to accommodate the fact that I’ll be doing fieldwork, conducting interviews, having research meetings and participating in a workshop on North American environmental politics.

Recent Comments