One of the skills I teach my students and research assistants on a regular basis is a method to find new citations across the literature. That’s what I (and others) call citation tracing.

A paper I was reading said "there is a dearth of studies on street begging, and few if any analyse it's public policy implications" O RLY? pic.twitter.com/HKEijX3oX4

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) January 29, 2018

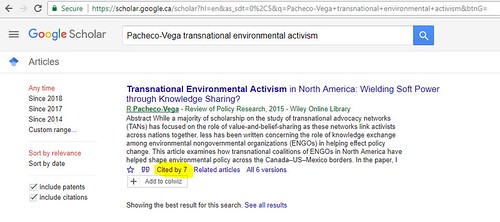

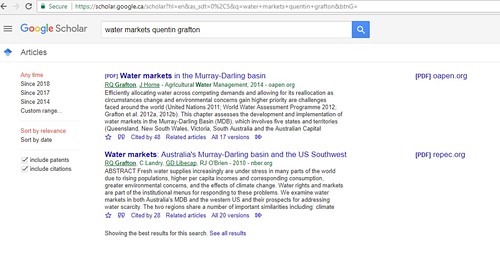

The examples I use here come from a Google Scholar search, but you can extend the method to Web of Science, WebMD, and other databases.

Forward citation tracing:

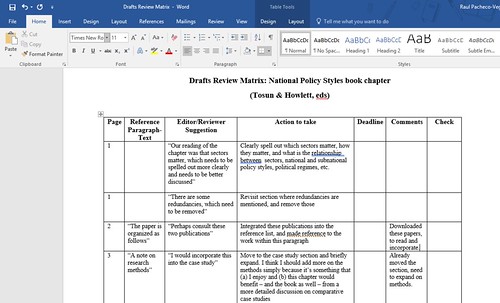

Refers to the process of finding the newest articles, books or book chapters that cite a particular paper, book, or book chapter. I call it “forward citation tracing” because you are going forward from the date when the reference you’re alluding was published. So, for example, a forward citation tracing on my 2015 Review of Policy Research paper on transnational environmental activism will give me 7 citations, which I can then look through in order to see

What do I mean by Forward Citation Tracing and Backward Citation Tracing? This one is forward (finding the newest articles that cite the one I am looking at by looking at Cited By on Google Scholar) pic.twitter.com/yGxBOFIQ6P

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) January 29, 2018

Doing a forward citation tracing exercise can allow us to stay in touch with the most relevant research that is following a specific topic.

Backward citation tracing:

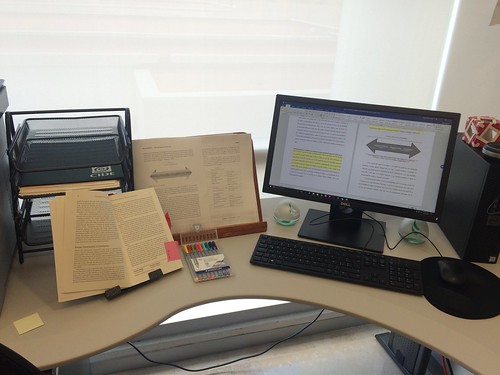

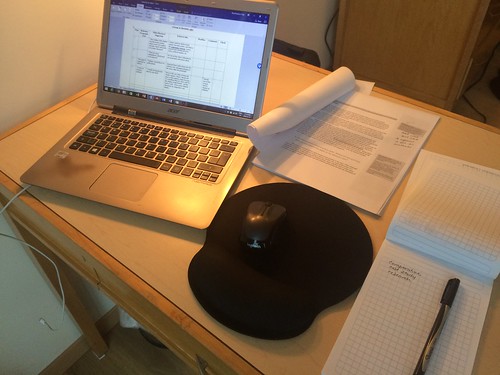

And this is Backward Citation Tracing (which authors does the paper I'm currently reading cite, that I might find interesting?) Don't laugh at my scribbles. I'm in a rush to finish writing a paper and I can't copy-and-paste typed text or edit-on-the-spot. pic.twitter.com/ViEKXh9gkZ

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) January 29, 2018

For me, backward citation tracing is key because it allows me to see if an author has omitted any crucial citations, or whether I can learn more from the texts they cited. This is an important exercise for my students and research assistants as well because they can see why a particular article they’re reading has gaps.

Another way to call forward and backward citation tracing is “Ascendancy Searches” and “Descendency” – which is basically searching up and down for citations.

When you have poor library full text access, this is invaluable when asking students to find 5 primary studies. Ascendency searches—who has cited this paper since its publication. Decendency searches— what papers did the paper you are reading cite? https://t.co/r8LaaiMoFY

— Academics Write (@academicswrite) January 29, 2018

Recent Comments