I have been travelling non-stop since January 2018 even though I had promised myself I would not do this ever again. But my scholarly research takes me to a number of places, including San Francisco last week for the 2018 meeting of the International Studies Association (ISA) and this week to the 2018 meeting of the American Association of Geographers (AAG).

As I have indicated before, I use conferences to force me to write full papers that I then submit to journals, or book chapters for books in which I have committed to participate. The past week and this week I have also been incredibly ill, with a cold and flu that I got during Holy Week (Easter Weekend) and then happened to get worse during my stay in San Francisco. This week, I am in New Orleans and luckily, heavily medicated and healthy again (or at least on the tail end of this awful illness). But I had not written, consistently. And even in previous weeks, my written output had been pretty minimal.

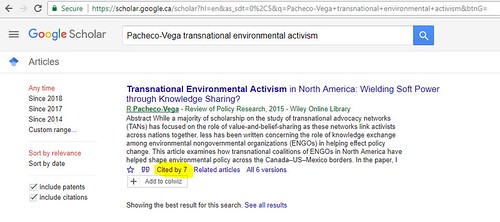

This is why I champion sentences and paragraphs as better measures of progress https://t.co/vbHefr5nAK also, my post was inspired by @tseenster 's @researchwhisper Your Word Count Means NOTHING to ME https://t.co/VgtcTvTpFM

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 27, 2018

The truth is that when I am not healthy, I don’t push myself at all. If I need to take time off from waking up at 4:00am and writing for two hours, I do it. I simply sleep in, and next day or the day after, I start again. But what I’ve found this year is that I have been able to write consistently and produce more than 34,000 new words (yes, that’s thirty four thousand words) by the end of March simply by setting small writing goals.

I have written 34,000 words since the beginning of the year. #AcWri #GetYourManuscriptOut

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 23, 2018

The truth is, I’ve managed to write that many words by writing in memorandums, and setting very small goals. 125 words, 250 words. 15 minutes of continuous writing. Anything that will make my work move forward, I’ll take it. That’s also why I champion a new metric of success: instead of fixating on words written, or hours spent we could focus on sentences and paragraphs crafted.

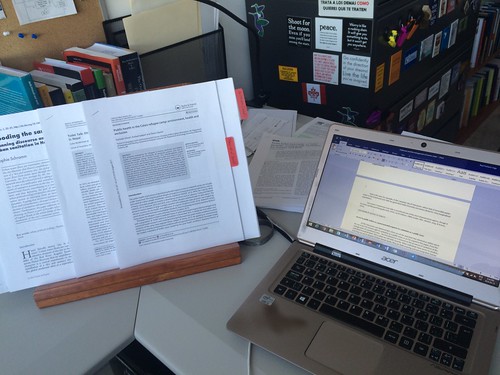

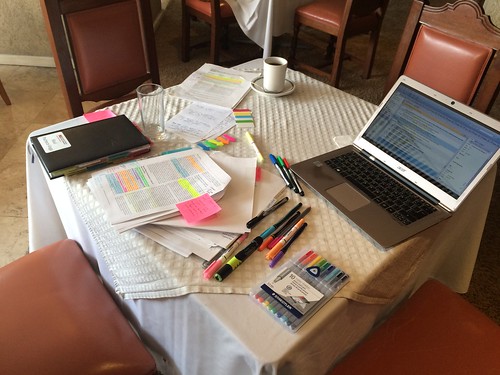

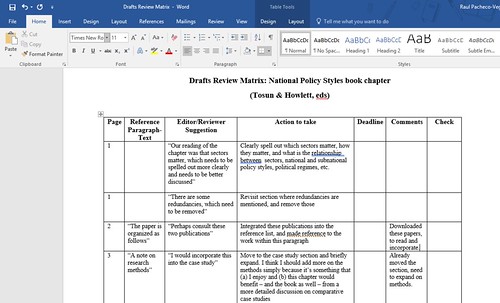

These are screenshots of the folders where I save files for the papers I've been writing. Specifically, this is for my #AAG2018 paper. I set small #AcWri targets (125-250 words, 4-5 paragraphs) because I know sometimes I just don't have it in me to write A LOT. I wrote 11 memos. pic.twitter.com/762BDi7pKI

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 30, 2018

One of the reasons why I am a big fan of small goals for everything (reading, 1 article per day, do an AIC Content Extraction and then write a Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump (CSED) row entry, what I call the AIC-CSED reading combo, writing for 15-30 minutes, drafting 125 new words) is because it sustains what Joli Jensen calls “frequent, low-stakes contact with a writing project” (read my notes on Jensen’s Write No Matter What here).

Besides adding up over time, writing for just 15 minutes/day also keeps the writing habit going, which presumably leads to even more writing time down the road.

— mjmottajr (@mjmottajr) April 6, 2018

Setting small writing goals (125 words, 15 minutes of writing) or reading (1 article per day, 1 AIC-CSED per day) allows us to stop berating ourselves for “not being productive enough”. That’s one reason why I love Tseen Kho’s article “Your Word Count Means Nothing to Me”. It’s important to remember that each person is different and that we all have different writing, reading, and researching practices. Hopefully this strategy will be helpful to others who, like me, experience fear when trying to tackle a daunting large research project.

Recent Comments