Despite the fact that I’m super organised and systematic, things get out of hand sometimes, particularly with all the travel I need to do, and all the students of mine that are graduating this semester, my teaching (I used to teach only in the Fall, but this Spring I had to teach because my students asked for my class, Comparative Public Policy and Administration), leading my water conflicts project, and sending out R&Rs. I’ve spent some time this month doing what many people call “spring cleaning” both at my campus office and at my house in Aguascalientes, and both mentally and physically. I gave away excess stationery, I donated clothes to charities, I prepared a clean, organised, physical copy of my readings packet for Comparative Public Policy and Administration, as I have a project that I will use them for.

Despite the fact that I’m super organised and systematic, things get out of hand sometimes, particularly with all the travel I need to do, and all the students of mine that are graduating this semester, my teaching (I used to teach only in the Fall, but this Spring I had to teach because my students asked for my class, Comparative Public Policy and Administration), leading my water conflicts project, and sending out R&Rs. I’ve spent some time this month doing what many people call “spring cleaning” both at my campus office and at my house in Aguascalientes, and both mentally and physically. I gave away excess stationery, I donated clothes to charities, I prepared a clean, organised, physical copy of my readings packet for Comparative Public Policy and Administration, as I have a project that I will use them for.

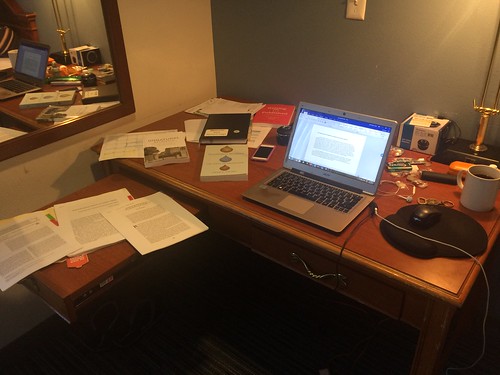

I reorganised my books. I cleaned my whiteboards and rearranged items on there to better reflect what I needed to keep track of. I packed away magazine holders with journal articles I no longer was using or that I wouldn’t use for an extended period of time.

Physical spring cleaning to me has meant that I have donated a lot of stuff that I did not use. Mentally engaging in spring cleaning means that I have started to change habits that I thought were good but in fact were hindering my growth. As a grand-child of military men, and someone who was raised with strict discipline, habits are a fundamental component of my life. Having neat and clean and organised work spaces is a fundamental component of my life.

Live shot of my home office at my Mom's (contrast with the fresh hell of the New York Review of Books' office) pic.twitter.com/wI1YrHPzIn

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 5, 2018

I wake up at 4 in the morning and start writing because that’s the habit that has gotten me published. A similar habit got me through my PhD. I spend weekends with my parents because that’s a habit that has enabled me to stay sane and healthy throughout my professional life. I keep an active and healthy social life because that’s a habit that forces me to take time for myself and reminds me of how lucky and blessed I am to have the life I do and to be able to do what I love and get paid for it.

I focus on completing 2 Things A Day before I have to deal with the massive influx of emails and meetings that academic life brings to me. I KonMari my academic life on a regular basis because that’s what keeps me able to work on clean surfaces and feel at peace.

I am definitely not someone who likes pop-psych nor do I believe in “woo-woo” theories, but I’ll credit Gretchen Rubin’s Better than Before, Charles Duggin’s The Power of Habits, and Stephen Guise’s Mini-Habits for reminding me that my entire life has been built around habits, and that it is important to revisit those to ensure I am still doing what I love without losing myself in the entire process.

I usually don't recommend "self help" books, but The Power of Habit is a very solid read. pic.twitter.com/WCe5DCfoH3

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) June 13, 2017

Because to me, being systematic about what I do has always been about making time for what matters to me (as I shared my views with Tierney Wisniewski on how everything needs preparation time). I also shared my views on orderly desks versus messy desks with Dr. Lisa Bryant. I need order because good organisation, productive habits and discipline are (to me) pathways to a more fun life.

Absolutely! As @bfwriter said about me (and her intuition was right) – I was raised with order & discipline as pathways to more fun life ?? https://t.co/34NjR75nTY

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 5, 2018

And really, the more disciplined I am, the more fun I have. Dr. Steve Shaw seems to agree with me.

Seems counter-intuitive, but the more rigid and disciplined my work habits the more creative my work becomes. pic.twitter.com/tR6NNybWgJ

— Steven R. Shaw (@Shawpsych) April 13, 2016

Recent Comments