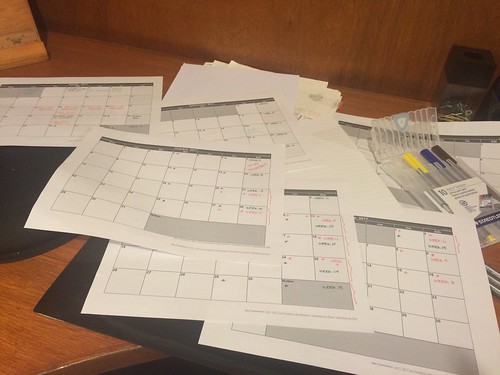

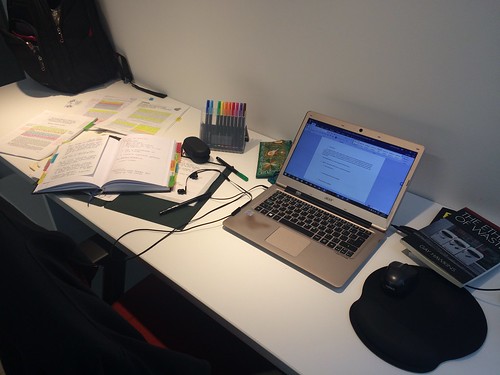

As most of those who read my blog and follow me on Twitter know, I’m very systematic about what I do and how I plan. My annual programme (which I create using printed monthly calendars and my Everything Notebook has the major milestones, but as time goes by, and things get post-poned, plans get derailed, or additional obligations get added, I need to make adjustments. Some are major, a few are minor.

I have two major moments of strategic workload readjustment. The first one is at the beginning of the month, where I look at my yearly plan as I broke it down per month, and then check commitments, verifying whether I missed something important by some odd reason. Since we are almost in November, this is the right week for me to revise my Monthly Plan and reassess what my commitments are and which ones I need to fulfil and what obligations I need to say no to. I check my Monthly Calendar every week, but sometimes I need to make changes even in that one, because I get invited to give keynote talks, participate in workshops, attend student progress meetings, etc. So, by the end of the previous month, while hopeful that nothing in my calendar will change, I am also aware that things may get added on to my schedule or shifted around.

Systematic planners: do you revisit monthly goals today (September 1st, Saturday) or wait until Monday September 3rd? Or did you do that yesterday August 31st? Or do you do it on Sunday?

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) September 1, 2018

The second moment of To-Do’s review for me is either on Monday morning or Sunday night. Throughout October (a perfect month for experimenting as it started on a Monday) I have experimented switching it over between revising my plan for the week on Mondays (as soon as I get to the office, or as soon as I wake up at home and start working) and then on Sundays. I’ve found that planning my week on the Sunday night allows me to hit the ground running on Monday. I probably have carried this strategy from my doctoral student days, when (if I needed to work over the weekend) I used to work Sundays instead of Saturdays (a strategy I recommend to my own students).

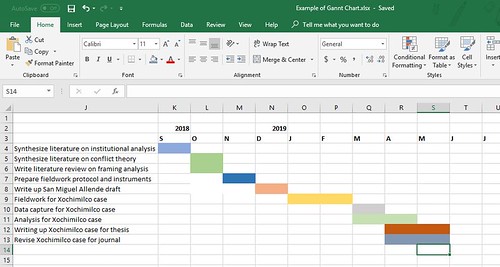

In previous years, I booked Every Single Minute of My Life. It didn't go well. Now, what I do is, on Sunday night,, I book meetings, writing time, and fieldwork and other stuff I KNOW already is scheduled. Then I leave free time where I can insert things I need to do. pic.twitter.com/CutIbAXqYe

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) January 15, 2018

I have to admit that Sunday night has worked much better for me than Monday morning. For one, it doesn’t intrude on my early morning writing/reading process. For two, it allows me to quickly glance at my daily plan and know exactly what I’m doing and what time. Hopefully this strategy will work for others too.

Recent Comments