When I was in graduate school, I discovered Endnote. Not only did I discover it, I actually bought a copy at the student price and became absolutely dependent on it. I taught courses to my fellow graduate students on how to use Endnote. I wrote my PhD dissertation using Endnote, as well as many, many papers. I now regret having tied my life to this reference manager because I have struggled to find another one that works as well as Endnote used to work.

When I was in graduate school, I discovered Endnote. Not only did I discover it, I actually bought a copy at the student price and became absolutely dependent on it. I taught courses to my fellow graduate students on how to use Endnote. I wrote my PhD dissertation using Endnote, as well as many, many papers. I now regret having tied my life to this reference manager because I have struggled to find another one that works as well as Endnote used to work.

A lot of people have recommended Zotero (which I have tried and didn’t love because I found the interface clunky, but I absolutely admire because it is open source and a labour of love, so I do recommend it to other researchers) but I settled for Mendeley, which is the software most of my coauthors use too.

I do pay for more Mendeley storage, so I don’t use the free version, but I think the features I will describe here are the most relevant ones too. I also don’t have the time to do a Zotero vs Mendeley vs Endnote vs Refworks vs Citavi vs God-Knows-The-Name-of-Other-Citation-Managers. I’m doing this guide mostly for my own students and research assistants, though I do share it with the world. And yes, I’ve had problems with Mendeley, and yes, I am pretty sure I am not using it to its fullest potential.

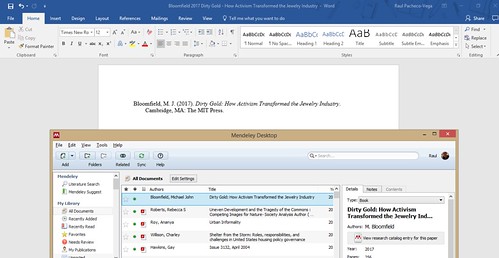

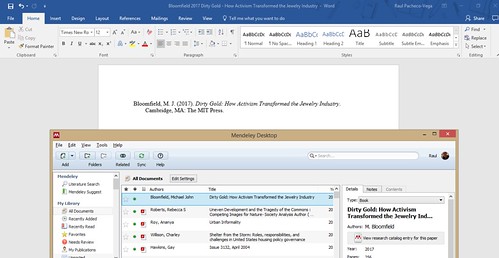

I use Mendeley for two main things: to store my PDFs and to use its Cite-O-Matic feature to automagically insert the references in the proper page and do the reformatting for me. Because it works with Micro$oft Word, it’s fantastic for my workflow (and no, please don’t recommend Scrivener because I also have already tried it and it didn’t work out). The Cite-O-Matic (or Endnote’s Cite-As-You-Write) is the one feature that I love the most about Mendeley. What is missing from Mendeley is Endnote’s ease of replication of citations (e.g. you need to write entries for EACH book chapter instead of simply making a duplicate and editing the fields, as you would do in EndNote). Also, in Endnote you could do footnote-style citation super, super easily (I am told you can do this with Mendeley now, but I am not sure how to do it, but happy to hear from people on this issue – email me instead of commenting!)

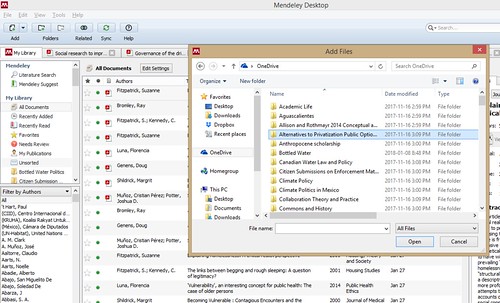

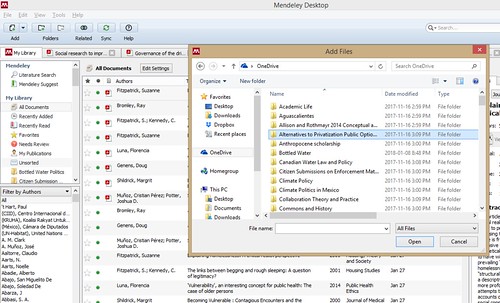

Anyways, the way in which I use Mendeley is as follows: Every paper of mine has a folder, and a sub-folder called “PDFs”, where I store every single PDF related to a particular paper. I know this creates duplication, but that’s how I work and how I’ve managed to write everything I’ve published since 2011. Anyhow, using Mendeley’s “Watch This Folder“, I ensure that Mendeley automatically uploads all PDFs related to a particular paper.

Obvious issue is that if the metadata come wrong, it’ll be harder for you to clean the reference.

You can add PDFs or entries automatically (with Import PDFs/Filesor Watch Folder), or you can add each individually by inserting the text into the proper fields on Mendeley as I show below.

I have specific purposes for each digital tool, as I show here. I do use Dropbox, Evernote, and Mendeley, as well as Excel and Word.

Before you use Cite-O-Matic, you need to “clean” your references. Cleaning a reference refers to the process of ensuring that Mendeley’s fields and choice of output are appropriate. In the case shown below, once the PDF is uploaded, all fields are loaded with garbage. You need to clean the reference by substituting the correct text in each field.

Every modification you make to the database, you should synchronize it since Mendeley keeps PDFs in the cloud (though you can also use the Desktop version, which is what I use). You can use Mendeley to insert citations automatically with Cite-O-Matic, or copy-and-paste a number of citations properly formatted, as I show below.

I do all the name-titling of my PDFs by hand, but apparently Mendeley (and Zotero!) can do this automagically.

My workflow isn’t entirely digital. I use index cards, Everything Notebook, Excel, Mendeley, Word, Evernote, etc.

The ability to copy-and-paste formatted citations is incredible to create syllabi, bibliographies, etc.

BUT… the most powerful use of Mendeley I’ve seen is the Cite-O-Matic plugin that integrates with Micro$oft Word. Write some text, search your Mendeley database for the proper citation(s), and insert them into the text. Then click on “Create Bibliography” and VOILA you have a paper with citations properly attributed and a bibliography properly formatted.

I should note that to add page numbers, you need to edit the reference manually and ask Mendeley to preserve it.

So this is how I use Mendeley in my academic writing as a reference manager and a citation manager, and I hope this mini-guide with the mere basics (I’m sure Mendeley has many other features I am missing) will help my own students, research assistants, and colleagues, as well as other people who may want to test-drive Mendeley.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: I have absolutely no connection to Mendeley, I’ve had MANY conflicts with them and have complained to them quite vocally on Twitter when Mendeley hasn’t worked properly, and I pay out of my own pocket for my own paid additional storage. And yes, I’m aware that they were acquired by Elsevier. So, no, I’m not really reviewing Mendeley, nor providing a favourable commentary on the program as much as describing how I use it to make it work for me.

Recent Comments