NOTE: This post is aimed both at undergraduate students AND educators. Obviously graduate students can also draw some insights from this post.

I’ve always thought that one doesn’t really learn “how to read” until one practices for an extended period of time with a broad range of sources. I think that the biggest challenge we face is knowing exactly how WE (faculty, professors, educators) read and then, transmit our heuristics to our students.

I’ve wanted to write a blog post on how to take good notes geared towards undergraduate students, and the first thought that crossed my mind was: “I have not been an undergraduate for SO LONG, how am I going to show my students how to take good notes if it’s been so long since *I* took class notes?“. I had the same feeling about writing a blog post on how to read for undergraduate students, until just recently.

A few weeks ago, Dr. Eve Ewing (@EveEwing on Twitter) requested resources on how to do “active reading”. You can click on her tweet, shown below, to display a very long list of resources and a fantastic thread of responses by many educators.

profs – do you have any resources you share with students on how to read an academic article? strategies for active reading, annotating, retention, skimming thoughtfully, stuff like that?

— wikipedia brown ||| abolish ICE. (@eveewing) June 25, 2019

As I mentioned on Twitter, I do not research the actual cognitive processes of reading/writing nor do I teach composition/rhetoric/writing as an individual subject. I teach my students how to read and write policy stuff. My students read literature from a broad range of disciplines: economics, history, political science, policy sciences, law, etc. They DO take a series of courses on argumentative writing.

HOWEVER, in my Public Policy Analysis class, I ensure that they know how to read and write, and I try really hard to teach them how to write well, not only policy analytical material, but generally speaking, research papers, memorandums, etc. You can access my resources on Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management here.

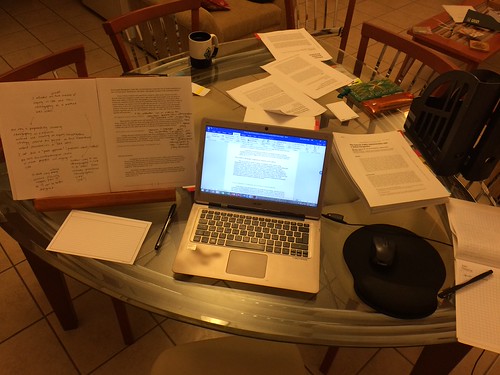

I devote a substantial amount of time to teaching them the basic things I believe are important for ALL students at all levels (undergraduate and graduate), not only the things they may need in my class. I show them how to write synthetic notes, how to write memorandums, how to synthesize their research in an Excel dump and a whole lot of reading strategies, literature review writing processes and note-taking techniques. I do this because I know they’ll be confronted with writing a thesis right after my class, I want them to be prepared.

My suggestions for undergraduate students on reading teachniques are therefore scaffolded, as I describe below:

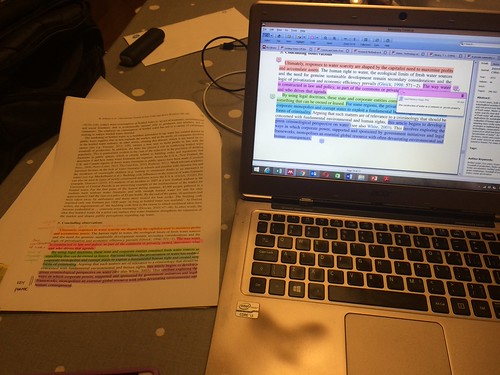

You can disagree with me and you’re welcome to do so. I have a reason why I make my students and RAs read Graf & Birkenstein before I even teach them my six-levels colour-coded highlighting/scribbling scheme. I do this so that they can recognize ARGUMENTS. People assume they can.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) June 26, 2019

Once students are equipped with a series of templates on how to read and understand (AND WRITE) arguments, THEN you can expose them to scholarly literature in your field. (G&B is here https://t.co/Y7J4KyS0oR and if you have good Google Fu you will find a full PDF on the web.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) June 26, 2019

The “start your paragraph with a topic sentence with the key idea within the paragraph” rule helps people read faster through by using a simple heuristics. When you bury your key idea within the middle of a paragraph, you’re asking the student to scramble and do a deep dive.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) June 26, 2019

I therefore would encourage undergraduate students who are looking for techniques on how to actively read to do the following:

1. Acquire Graf & Birkenstein’s “They Say/I Say” book.

2. Read said book (cover to cover).

3. Do the exercises suggested in that book as you go along.

4. Once you have discerned the difference between describing and analyzing, and how to write arguments, you should be able to identify key ideas within paragraphs more easily even if they’re not a topic sentence (e.g. they’re not in the first sentence of the paragraph).

5. Read. Read a bit more. Read some more. Perhaps my Reading Strategies and Note-Taking Techniques will be useful to you.

6. Check all the resources provided by faculty in response to Dr. Eve Ewing’s tweet (you can check them by clicking on this hyperlink).

7. Rinse and repeat.

I strongly believe that the best way to improve your reading is by doing it on a regular basis. Remember, reading IS part of the job. Hopefully these suggestions and those linked in Dr. Ewing’s tweet will be helpful!

Recent Comments