This blog post comes from a Twitter thread I did on snippets of wisdom that I have drawn from a broad range of writers. It’s like the synthesis/distillation of all (or most of) the books about writing that I have read. This wisdom applies to writers of books, articles, or theses.

MAKING SPACE: Most authors I have read (Joli Jensen, Eviatar Zerubavel, Stephen King, Helen Sword) recommend that people carve a physical space to do their writing. This ritualistic approach may not work for everyone, it does for me. I have 3 spaces where I work (home, office), and my home office in my childhood bedroom at my Mom’s house.

I try really, really hard NOT to work in my dining table (I now have a big enough house that I can do this, but even when I lived in Vancouver in a shoebox, I had a little alcove that I used to JUST write my doctoral dissertation). The point that Stephen King and Joli Jensen in particular make is that you need to CARVE that space out of whatever you have available at the moment.

MAKING TIME. The authors I mentioned, plus Bolker and Boyle Single, all suggest that you should designate (or carve) *SOME* time to sustain a writing practice. Most people say 15 minutes is not even enough to launch the laptop. Probably, BUT I have found that if I am able to devote at least 15-30 mins to writing, I feel like it helps ME move my work forward.

I try to always remind people that nobody has the same schedule. Contingent faculty cobbling courses together don’t have the luxury of carving time. Let’s fight this. I want an academia where contingent faculty are moved up to permanent contracts, where they are paid decent wages, and where they are able to carve time to write instead of having to struggle to make ends meet.

At any rate, for me, carving chunks of time and creating a physical space are also associated with creating a “mental space”. My brain needs to be “in the right head space” to write.

ENERGY: You need the right amount of energy to write. This is something I realized when I started with my chronic fatigue/pain. I don’t always have the energy to write. Again, most writers (but especially Jensen) suggest that we acknowledge that in order to write we need to be in decent/optimal energy/health state.

Nobody can provide a magic formula for how to develop the energy to write simply because we are all different (and I recommend that you read Chronically Academic, so you can understand the struggles of individuals facing chronic illness, and many of the wonderful folks who are courageous and brave and speak out about mental health issues. Let’s accept that academia is a highly competitive environment that has at the very least the potential to have very negative effects on people. Let’s also admit that to write we need energy/mental state.

PROCESS: Zerubavel, Dunleavy, Single, Sword and Jensen all emphasize that we should have a writing practice. John Warner’s The Writer’s Practice provides some examples of how to develop one, I do have mine (you can check blog posts I’ve written on this topic by clicking on this link)

There is huge variation across writing practices. Some authors recommend writing every day (Jensen, Zinsser) because, you know, it’s like a muscle, others (Zerubavel) suggest that you block out when you CAN’T write and make the time for writing based on those “Can’t Do” slots.

PREPARATION AND PLANNING – this is the part that I see very clearly in Zerubavel, Single, Jensen, Dunleavy, Heard, Sternberg: you need to pre-write (which includes outlining, reading, researching, synthesizing literature, gathering data, analyzing, etc.) before writing.

AUDIENCE: Warner, Germano, Rabiner and Fortunato, Zinsser, Kamler and Thomson all insist that part of your preparation includes determining the audience. This is also why I love Josh Bernoff’s Writing Without Bullshit. Our audience wants (for the most part) clear prose, although I know a few academics who seem to revel in writing obscure stuff.

QUALITY AND QUANTITY – Paul Silvia tells you that you should write a lot, which coincides with most advice (Bolker and Dunleavy included) that says that “the best dissertation is the done dissertation”. I don’t know if you should write a lot, but what works for me instead is breaking down the work in smaller components and then engage with those work packets.

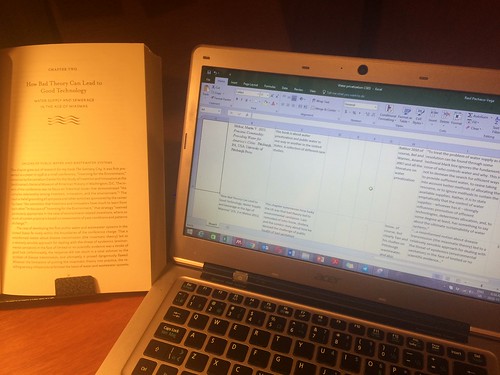

I write memorandums, synthetic notes, rows in my Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump. I try to write a bit every day (I’m not a “words per day guy” for the most part). Most advice does suggest “words per day” as a metric, but your mileage may vary. I encourage my students and research assistants to look at “paragraphs and sentences completed” instead.

On quality: I’ve seen some very senior academics say “I don’t want to read a half-baked paper when peer-reviewing”. I’m going to try to say this in the nicest way possible: “Remember that your definition of half-baked may not be that of other people, please provide kind, concise and actionable feedback on how someone can turn a half-baked paper into something that you’d like to read”. Particularly senior people, you’ve been in this business longer. Please help out whenever you can.

SUMMARY: There is no perfect approach to writing. I examine my own process regularly, adjust, change, try different things. Waking up early to write works for me, writing every day works for me, reading about how to improve my writing works for me.

YOU DO YOU.

And remember: we all struggle with our writing.

Recent Comments