I am very much on record with my view that books should be read in-depth, and that skimming is an important strategy out of a broad repertoire of reading heuristics. Although, I’ll admit that after reading “How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading” by Adler and Van Doren, my priors have been updated. I don’t think I can say the same thing that I used to say before: teach people to read in-depth before skimming. I think one can use Adler and Van Doren’s Levels of Reading as sequencing heuristics to teach various strategies. You can read an excerpt from the book here, specifically the table of contents.

That said, I still insist that we ought to avoid teaching students to ONLY skim. OF COURSE, we also need to learn and teach how to triage our reading workload, too. It’s equally problematic to insist that they ONLY read in-depth. I think we ought to provide them with a broad range of reading strategies (which is why I write so often about the topic – also in hopes to help my students develop these skills).

Someone on Twitter, I can’t recall whom, asked me if I had ever read Adler and Van Doren’s book. Well, no, I hadn’t. So I made some time last night to go through it. As I’ve noted before, I am an extremely fast reader, so I could absorb the entire 350 pages in a very short period of time. I wrote a Twitter thread summarizing my reading notes from the book.

First off: it’s a HUGE book. On how to read books. YIKES.

Adler and Van Doren’s “How to Read a Book” has TWENTY ONE CHAPTERS.

21.

Fellow professors: I recognize that I don’t teach writing, but if I did, I would need a semester-long class (16 weeks) assigning more than one chapter per week as core reading.

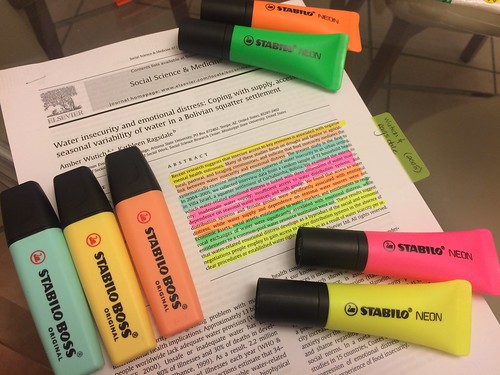

Seriously?! 😂 pic.twitter.com/0MRUKh7wxe

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 30, 2019

The above said, it IS a great book.

There’s an inherent assumption in Adler and Van Doren’s approach to reading a book. You’ve at least achieved skills and competencies of US and Canadian ninth grade.

This is problematic for non-native speakers of English who now have to read A LOT of stuff quickly under pressure pic.twitter.com/y3FKuRkTN2

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 30, 2019

So, you may wonder/ask me: “would I recommend this book?”

Sure. OF COURSE!

Jesus, people.

Do you think I would spend my time reading a book about reading books and then write a Twitter thread at 5:20 in the morning Mexico City time, my prime writing time, just for naught? pic.twitter.com/WDlnRH4czk

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 30, 2019

So, you may ask me: “professor Pacheco-Vega, what’s the strategy then to use Adler and Van Doren?”. Well, grad you asked.

This is the strategy *I* plan to use with my graduate students (remember, they’re all Spanish-speakers, who have learned English as a second language)

For graduate students

1) Give a 1 lecture summary of the entire book, maybe in a workshop format.

2) Produce a Coles’ Notes summary and,

3) Give my students my Coles’ Notes, have them read them, then have them read AVD up until the “reading different types of material” chapter (16, I think?)

4) Have THEM write Synthetic Notes of each chapter (to note, I won’t let them do AIC skim reads. These synthetic notes should be mini-memorandums on ADV).

What would be my strategy for undergraduates?

Most institutions (at least mine does) have an “Argumentative Writing” course. What I plan to do is tell the professor about this book, and suggest that they replicate my strategy up (1 and 2) but then assign a chapter per week.

At the core, AVD is about developing a repertoire of reading strategies, which I emphasized last week we need to do https://t.co/dQvzmr9lZx (I also have a page on reading strategies for undergrads) https://t.co/0Dnb2ITySI

Adler and Van Doren’s book would be the guide for HOW TO

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 30, 2019

Bottom line: like Adler and Van Doren, we need to teach different levels of reading and various types of strategies to achieve our own learning goals and those of our students. 10/10 do recommend.

Bottom line: My assessment of AVD H2RAB

YES, WORTH READING, WORTH ASSIGNING, WORTH USING IT AS A TEACHING TOOL.

AND… I found it on Amazon super cheap (I know, we hate Amazon, it’s evil, but … https://t.co/8Ctd22iH3n)

</end thread>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 30, 2019

Recent Comments