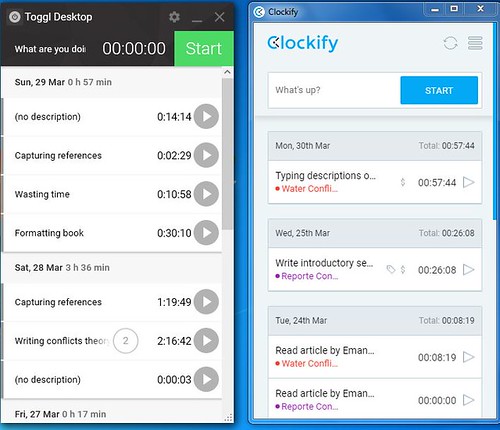

This morning I wrote a Twitter thread about how my research on the politics of bottled water can help us understand why individuals hoard toilet paper, N95 masks, gloves and other protective equipment. I think I can get something more scholarly out of this, but at least, I wanted to get some thoughts down on paper.

Some people (particularly those fond of specific governments and parties) seem to be upset and/or surprised about the fact that certain populations have taken steps to protect themselves from the COVID-19 pandemic well before governments started visibily proactive measures.

Hoarding toilet paper, face masks, and important protective products for health care workers is rightfully seen as “doing something wrong” (it IS wrong considering that so many health care workers, immunocompromised individuals and vulnerable communities are unable to access protective equipment right now). Using my research on the politics of bottled water, let me explain to you why people are doing this, and why they were anticipating that their governments would not be able to provide protection for them so they had to take it upon themselves to protect their loved ones and their own well-being.

Mexico is the world’s top per capita consumer of bottled water. One of the key factors that drove this phenomenon is the government’s absolute dereliction of duty. After the 1985 Mexico City earth quake which left much of the city’s water delivery infrastructure network destroyed, the National Water Commission started PROMOTING bottled water consumption as a strategy for self-protection. or the Mexican government (and for many others across the globe) it’s much easier to transfer the responsibility of self-protection to the individual citizen. This is what I call an abdication of duty.

Mexico is the world’s top per capita consumer of bottled water. One of the key factors that drove this phenomenon is the government’s absolute dereliction of duty. After the 1985 Mexico City earth quake which left much of the city’s water delivery infrastructure network destroyed, the National Water Commission started PROMOTING bottled water consumption as a strategy for self-protection. or the Mexican government (and for many others across the globe) it’s much easier to transfer the responsibility of self-protection to the individual citizen. This is what I call an abdication of duty.

Individuals do this based on what Andrew Szasz calls “inverse quarantine” (or reverse quarantine). Szasz notes a peculiar phenomenon in the consumption of bottled water, organic food, and individual oxygen tanks.

These are self-protective strategies where citizens realize that government is not going to protect them, so they need to protect themselves.

As both Szasz and I note (independently), the problem with this reverse quarantine strategy is that citizens stop challenging their governments to provide the services they need. This is a problem, because of inequality and uneven distribution of wealth https://t.co/dXnsR7TrP9

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 18, 2020

You (broadly construed you) may be able to protect yourself by buying bottled water (or organic food, or individual oxygen tanks, or your own N95 masks, gloves, etc.) But inequality means that not everyone can do what you can, i.e. protect themselves. So that’s where government needs to step in. If we stop demanding public services from government, those who are most vulnerable won’t be able to access those services. It doesn’t matter if we don’t use them (i.e. if you go to a private hospital).

We still need a functioning health system. Same with my other two loves and research interests, water and waste. We need a functioning government that is able to adapt fast to the rapidly changing needs of a heterogeneous set of populations with diverging and wildly varying needs. Reverse quarantine only gets us so far.

This reverse quarantine lens can also be transferred to understanding why sub-national units have gone against the federal government in their policy responses: They’re reverse quarantining their populations. If the federal government won’t provide for their citizens, then heir subnational counterparts (states, cities, municipalities, provinces, autonomous communities) will do it instead of the federal government.

And that’s just one aspect where studying the politics of bottled water can give us great insight into how policy responses to a pandemic can emerge from civil society groups or subnational units.

Recent Comments