I need to stay on top of several literatures and finish several papers, yet I have caved to the “I am too overwhelmed with teaching” reality. So in order to force myself to spend some time every morning catching up with the literature, I decided to launch yet another #AICCSED Reading, Annotating and Systematizing Challenge. #AICCSED, admittedly an awkward acronym, stands for a combination of the AIC Content Extraction Method that I champion to skim articles (Abstract, Introduction, Conclusion) and my Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump (CSED) Method to Systematize the Literature. Both systems combined allow us to stay on top of the vast volume scholarship that is being published at absurdly rapid rates.

Carving time to read is hard enough, so I decided to promote processing articles using a combination of AIC+CSED methods on an regular basis. This strategy is useful if you have a pile of articles and book chapters that you want to read but you keep putting off the time to do it. It also works if you want to stay on top of the literature on a regular (daily, fortnightly, weekly).

Yet the problem for me is that unless I am being forced to do it, I sometimes forget that I need to read in order to write (yes, I know I champion this approach all the time, yet I also fall prey to the multiple demands on our time!). Therefore, I decided to give myself a nudge and engage in an #AICCSED Reading, Annotating and Systematizing Challenge.

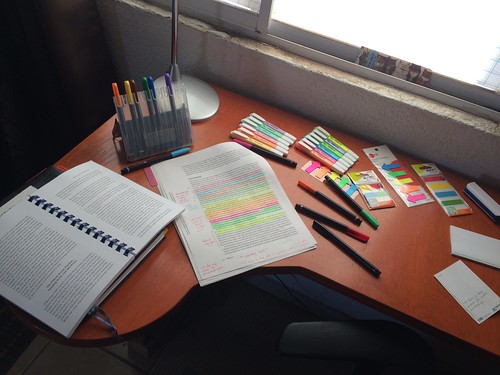

I am going to read one article every single morning (NEW ARTICLE, NOT SOMETHING I HAVE ASSIGNED FOR MY CLASSES, LET ME JUST MENTION THIS), annotate it and highlight it, and then I’m going to drop my notes in an Excel Dump row. I’m then going to post it on Twitter.

I’ve done this challenge several times over the past few years, and it’s always turned out well. A few people end up jumping on the bandwagon and it becomes quite useful to them because by the end of the challenge they’ve got notes on 30 articles, and they have read and absorbed at least the Abstract, Introduction and Conclusion of 30 articles.

This time around, I decided to showcase the amount of work involved in doing a daily #AICCSED. I wrote a Twitter thread from where I extract to showcase the method here. I do this process following these steps:

- I download the paper and upload the PDF to Mendeley.

- I clean the reference in Mendeley.

- I print the paper (double-sided, always).

- I read the Abstract, and highlight it.

- I annotate the Abstract, write some notes on the margins.

- I read the Introduction, highlight passages and sentences that I find useful and important.

- I annotate the Introduction.

- I read the Conclusion, highlight and annotate.

- I drop my notes in a Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump (CSED) associated with the topic I am reading. And voila!

In the Twitter thread that follows, I summarized my process for one article, so that people could see what they’re getting into when signing on . #AICCSED doesn’t require that you read the full article, but solely Abstract, Introduction and Conclusion (AIC). What you may find, however, is that you may in fact NEED to read the entire article or WANT to do so because it’s filled with important concepts and ideas.

I am considering if I want to do a Google Forms for this, as my good friend Luxana suggested.

For me, my simple system of #2ThingsADay often means that the only two things I get done in a day is reading a paper (and annotating) using the AIC method, and dropping it into a CSED spreadsheet. What we do in the #AICCSED challenge:

We drop a tweet reporting which article we read and we (often, not required) post a screenshot of the CSED (Excel Dump) row associated with said article.

What’s the purpose? To keep us reading, synthesizing and summarizing EVERY SINGLE DAY.

What an #AICCSED challenge is NOT – it’s not intended to stress you out – we’re in the midst of a pandemic, we’re short on time, we’re all stressed out. But if you can participate in the #AICCSED challenge, by the end of the month you will have 30 articles summarized in an Excel spreadsheet.

It requires some time investment and re-prioritization. For example, I MUST finish a book chapter on climate politics, literally TODAY. BUT… if I engage in the #AICCSED challenge, I want to read stuff on informal water, on waste and discards.

I normally do round months instead of saying “let’s do an #AICCSED fall semester challenge”. This semester, though, to help my student keep reading, I’m going to ask them to do the challenge themselves. It’s only ONE article a day on their actual thesis research.

Not a lot.

Again, I know we’re in a pandemic, and this is in no way meant to stress anybody out. It IS on the other hand intended to provide structure for people so they can keep reading and systematizing their materials.

Q – I can only do 1 a week.

A – GREAT, you’ll have 4 more articles!

Q – I can join #AICCSED but only infrequently

A – Fantastic! Whatever progress you make on staying on top of the metric tonne of readings we have to do is great

Q – I would like to do this once the beginning of the term is over

A – Fabulous. Join whenever you can!

Hopefully the #AICCSED Challenge will be of interest and helpful to you!

Recent Comments