Writing is hard. And writing field notes is hard, too. I don’t think that there is enough guidance on how to do it. I’ve written about the use of ethnographic fieldnotes in scholarly written output, but I don’t think I had ever written about how to write fieldnotes and how to teach or learn on your own how to write better field notes.

Given my extensive experience as an ethnographer and fieldworker, I felt that it was important that I wrote a Twitter thread (which I am now converting into a blog post) on how to write field notes, along with references and citations that might be useful for people to read.

While there is literature on fieldwork (and field notes/fieldnotes, whichever spelling you prefer), and on ethnographic fieldwork, I feel like there’s never an “orientation” on how to write good field notes. Here’s a partial bibliography I compiled. https://t.co/Omp2JE2T3V

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Weirdly enough, I sometimes forget what I’ve published, particularly on qualitative methods. Well, here is an editorial I wrote on how you can use fieldnotes to prompt you to write, particularly when you’re feeling blocked. Pay attention to what I cite. https://t.co/oDBHjlw6gt

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Over the past three weeks, in my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation class, we have covered Coding, Theming and Writing Field Notes and Analytic Memorandums. These are classic components of qualitative text analylsis, and I discussed them in great depth. I believe that’s part and parcel of QDA.

But I want to emphasize what Maxwell 2013, p. 91 says: “there is no cookbook for qualitative methods”. I keep telling my students that qualitative analysis is extremely iterative. We try something, we code one way, see if it “sticks”, code another way, reframe, rethink. pic.twitter.com/Iv0j2eH8as

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

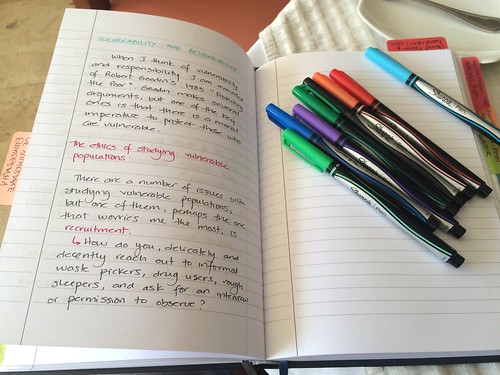

In my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation class, I went over what I believe is the core of a field note: I use a notebook, and on one side, I write my observations of whatever I am studying, alongside with the date and time. I make detailed notes (also noting on the left hand side of the page). Usually, the left hand side of the field notebook pages serves me to note my own emotions, the context, etc. This is not an uncommon approach (left hand side “emotions/context”, right hand side “phenomenon we are observing”) but others may use a different approach to mine.

As most of the respondents to my question of whether they would allow someone else to see and re-code their field notes noted, field notes are extremely personal, and may contain personal data that can be sensitive (all responses were AMAZING).

https://t.co/KI3fuPcihL— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

But in my view, that’s also part of why it’s so hard to teach how to write good field notes: many/most of us may not be willing to show anybody else our field notes (for privacy/sensitivity issues, but also because they are primarily for us). And yes, despite good books on field notes.

… I have come to regain love for other three books:

Sanjek https://t.co/KdT7W1PPuH

Vivanco: https://t.co/WrGlNIw4jW

Emerson, Fretz and Shaw: https://t.co/4LCAaxQ3Zv

To note: ALL three books are excellent on the topic of ethnographic field notes. None disappoints.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Now, here’s the thing: you can teach how to write field notes, and how to write GOOD field notes, but then there’s the question of how do you write good ETHNOGRAPHIES? As I have taught my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation students, my own personal bias is that a field note and an analytic memo are DIFFERENT.

Several authors agree with me (fieldnote is a record of my observations, analytic memo is a reflection of what I recorded in the fieldnote), including Saldaña 2013, p. 42, from where drew this quotation.

Here’s my personal view (RPV): we need to teach GOOD fieldnote writing. pic.twitter.com/bHXrf3I55j

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

But to teach how to write good fieldnotes we also need to educate our students on how to write excellent ethnographic prose. For that particular purpose I have two suggestions:

1) Read A LOT OF ETHNOGRAPHIES, particularly book-length.

2) Read books on how to write ethnography.

For (2), I have two books I want to recommend: Kristen Ghodsee’s “From Notes to Narrative” https://t.co/l5SJDByHV1

Ghodsee does something rarely done (from what I’ve read): she walks you from your fieldwork notebook scribbles to producing great ethnographies. Excellent book.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

And the second book is by Kirin Narayan, “Alive in the Writing” https://t.co/qCUayWzz7y

Narayan is spectacular in how she crafts narratives, but she also offers EXERCISES. “Here, this is how you do THIS in your writing”. Her writing is very didactic and easy to absorb.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Teaching Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation has already changed me and the term is not over yet. I have been able to spend a lot of time pondering and thinking about the craft of teaching how to do good qualitative research, and it has benefited me enormously.

So, my take home suggestions. If you want to learn how to write good field notes:

1) Read books on field note writing

2) Read books on writing ethnographies

3) Read well written ethnographies

4) Practice writing field notes

5) Practice writing analytic memorandums.

and…

6) Practice writing scholarly outputs.

Hopefully this blog post will be useful to readers interested in qualitative methods.

Can you recommend books on field note writinfg?