One of my former students asked me recently whether I had written anything on how to write a literature review, as he was asked to write one on a topic he hadn’t ever done research on (I do have a blog post on how to map an entirely new topic and write a literature review).

His request, and coming across another similar one over Twitter prompted me to reflect, first of all, if the structure of my Resources page and Literature Reviews subpage was not clear enough (I have written A TON of blog posts on the topic of reviewing the literature) and secondly, whether there was some sort of missing connection between what students are asked to do and the guidance that instructors provide. So this thread I wrote is aimed at tackling both issues.

… something I identified in an earlier thread and blog post – our students are EXPECTED to know how to do something, when nobody has taught them explicitly what it looks like, how to do it. https://t.co/WiqbcrCMY1 unless you’ve taught someone how to do a LR, you can’t expect it

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 8, 2019

… as a result, the process to generate each one of them is distinct / I have written on how to generate an annotated bibliography https://t.co/ECT6Rfw6I2 which is the first step I would expect anybody unfamiliar with LRs would do, just as a matter of training. BUT I also ask…

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 8, 2019

Before I go on with my strategy to teach someone how to do a literature review, I show them two diagrams that are important to me. The first one explains how the literature review is situated within the production of a scientific paper. This process applies to any other type of research output (a book, a dissertation, etc.)

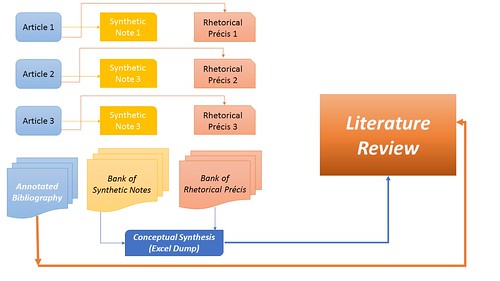

The second diagram that I share with my students and RAs is an overview of the different scholarly products we can generate (and their intermediate outputs): packages of rhetorical precis, sets of synthetic notes, folders filled with memorandums, annotated bibliographies, Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump tables, literature reviews (see diagram below).

In my own case, if I wanted to teach someone how to approach a new body of scholarly literature, in addition to teaching them Reading Strategies and Note-Taking Techniques, the sequence of blog posts that I would recommend they peruse (and I have used as teaching tools) would be (is):

- How to write a rhetorical precis

- How to skim/summarize an article using the AIC (Abstract, Introduction, Conclusion) content extraction technique

- How to develop a Synthetic Note

- How to write an Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump (CSED)

- Developing a literature review, based on 1-5

- Expanding a Synthetic Note into a full-fledged Memorandum

- Writing /robust/effective memorandums

I did write a blog post outlining step-by-step how I do literature reviews https://t.co/TZEegZtbEY and some of the most frequent questions I get asked by my students and RAs – I explain to them the different scholarly products I usually generate https://t.co/IhXJhBjaHQ

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 8, 2019

I find enormous value in (DTP, CSED, outlines) because students and researchers alike can all get lost and bogged down in the details, missing the forest for the trees. They’re useful for me as a supervisor and for my students and RAs.

Now, for instructors – what kind of guidance do we need to give students and research assistants?

Generally, I find that where students lack guidance is:

a) what is a LR?

b) how many sources?

c) how do I read/annotate/synthesize

d) what do you expect me to write (headings, sub headings, topics to cover)

e) when is a LR finished?All of these have idiosincratic responses

What do I mean by “idiosincratic responses”? Well, we all like different scholarly products our own way. There is NO SINGLE APPROACH to writing a literature review, which is why I suggest that those requesting it write a handout or offer at least verbal or hands-on guidance on topics, key authors, etc.

I think we ought to be explicit about what exactly we want from students and research assistants, and our preferred way of doing things, because sadly there is no standard operating procedure for this.

Same with the doctoral dissertation, or with any thesis.

</end thread>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 8, 2019

So, what does this guidance look like in practice? These tweets offer an overview of what my interaction with my PhD students looks like when we discuss LRs.

One of my (already graduated) doctoral students wanted to include a water-mining conflict in his dissertation. I don’t study mining (I took courses during my Masters, but I’m not familiar with the literature). BUT I knew mining and water conflict scholarship existed on Peru.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 9, 2019

Once he had read some of that work, I asked him to do forward and backward citation tracing until he reached some key authors on water and mining IN MEXICO (I know Aleida Azamar Alonso from UAM has published extensively on mining, but not so much on water). And so on…

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 9, 2019

With my graduate and undergraduate students, when I ask them to review the literature, I offer:

a) Key authors

b) Suggestions of keywords to search in databases

c) Links to my blog posts on how to do each step of the process

d) Sample questions/themes to expand on.</end>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 9, 2019

Hopefully this blog post, full with links to other posts I have written and to my Twitter thread will be helpful both for students and supervisors/professors.

I just want to thank you so much for documenting, you dont know how much you have helped