I was in Paris last week for an EGAP (Evidence in Politics and Governance) meeting and workshop, EGAP19. I am a member of EGAP and was invited to participate in this workshop, hosted by Dr. Daniel Rubenson (Ryerson University, on sabbatical at Sciences Po) on field experiments (though the main focus for this meeting was policy interventions). As I always do when I travel somewhere for a conference or a workshop, I also scheduled some meetings and did a bit of fieldwork.

Whenever I mention that I have been doing fieldwork in Paris, I get a mixed bag of reactions, ranging from “wow, how interesting to study Paris” and “well, isn’t that lucky, you get to do fieldwork in Paris” (almost implying some degree of ‘academic tourism’).

See? There is a research-based reason why I do fieldwork in Paris pic.twitter.com/SA45wAzjhH

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 7, 2017

I won’t deny that I absolutely love Paris, as it is a beautiful museum in and of its own. I have spent a lot of time in Paris, and done extensive fieldwork in the city, and I definitely wouldn’t mind living there for a while. But there are actual, real, research-based reasons to study Paris and its water history. In particular, for the topics I study (the governance of non-traditional common pool resources and the comparative politics of public service delivery), Paris is the perfect site for field research on water governance.

Paris offers an interesting research puzzle for those of us interested in the politics of water privatization, remunicipalization and alternative service delivery models: its water supply has been remunicipalized despite the fact that the two biggest water privatizing companies worldwide (Veolia and Suez Environnement) have their headquarters in Paris. France itself has been a pioneer in remunicipalization practices, as documented by Lobina, Hall and others.

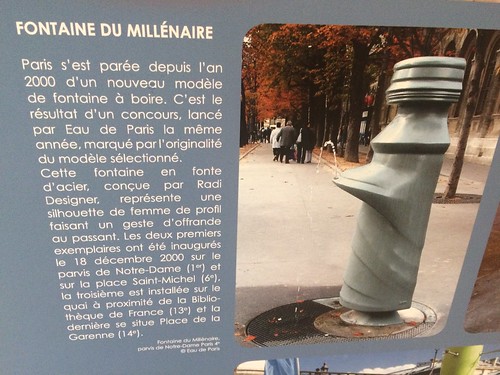

Paris also has a very long history of public water provision in the form of drinking water fountains (including some historical ones of the Wallace model). The photo below is taken from the Water Pavilion (“Le Pavillon de L’eau“), a water-focused museum maintained by Eau de Paris, the local water municipality. This photo showcases a “Millenial Fountain”, one of the newest models of water fountains. From my conversations with Paris residents, there is very little interest in bottled water in Paris, given that the tap water quality is quite good.

I am particularly interested in Paris not only because of the remunicipalization of its water utility (which in and of itself is an interesting case study), but also because there is some scholarship about the history of bottled water within France, which is relevant to my current research on the politics of bottled water. Some brands of premium bottled water are French (for example, Perrier‘s sparking water is quite popular worldwide) and while individual adoption of bottled water consumption practices doesn’t seem prevalent nor occurring nation-wide, there’s definitely a chance that it may happen in the future.

Overall, Paris is an excellent site for field research on water governance, and French scholars (as well as France-based) have produced a lot of really relevant work in the French language that also should be read by everyone who is interested in the topic.

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.