I am a member of the Public Outreach Committee of the International Studies Association’s Environmental Studies Section (ESS of ISA). At ISA 2018, recently held in San Francisco, I participated in a Publishing Roundtable organized by Dr. Beth DeSombre as part of our Speed Mentoring Series, which is organized by the Public Outreach Committee.

I was asked to participate because I do a lot of writing on academic prose, and because of my experience publishing journal articles, book chapters, and editing journals, so I was thrilled to contribute to these mentoring sessions, as they’re intended to help graduate students and early career scholars, but also established and seasoned academics. Over the course of the session, we all shared our own tips with doctoral students, postdoctoral researchers and assistant and associate professors who were writing book manuscripts and/or wanted to publish journal articles.

All participants shared lots of pearls of wisdom, but perhaps the one that stuck the most with me was that coming from the commissioning editor of Oxford University Press for politics, Angela Chnapko.

She suggested that we should read published books, particularly their introductions, to see how we could craft our book proposals and in turn, our own manuscripts. This piece of advice has stuck with me, and now that I’ve read about 45 books in the past 3 months, I’ve come to realize why she said what she said.

Thread on key piece of advice provided by an @OUPAcademic at the #ISA2018 Speed Mentoring table on Scholarly Publishing (thanks to my fellow Outreach Committee member Dr. @BethDeSombre for organizing and @ESS_of_ISA for sponsoring the session). The advice: READ BOOK INTRODUCTIONS

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

Reading the introduction to a published book gives you amazing insight into why an author undertook the project, how they went about the research, fieldwork, data analysis, etc., and what the book’s implications are for the specific body of scholarship we try to contribute to, for the field, and the discipline, as well as society at large.

Intuitively, I understood this. William Germano indicated it in his two books, From Dissertation to Book and Getting It Published, but it wasn’t until Angela said it that it all clicked in my head.

Read the book’s introduction.

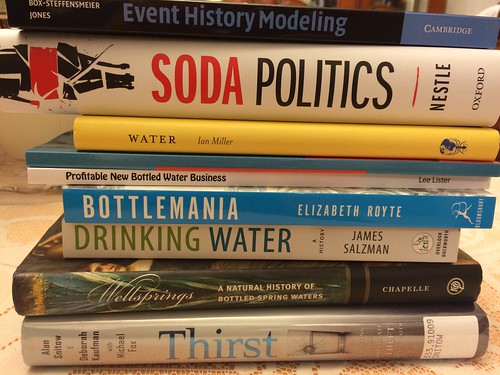

While I am writing my own book manuscripts, I would not feel comfortable showcasing my own work as an example for how you should write so what I did was take examples from a few books I had at my Mom’s house or that I was travelling with. These five examples are just a few, but the basic lesson stands: READ OTHER BOOKS’ INTRODUCTIONS IN ORDER TO LEARN HOW TO WRITE YOUR OWN.

In my thread, I provided an overview of three books’ introductions (the three I had purchased during AAG 2018). The first one was “Resigned Activism” by Anna Lora-Wainwright.

First example is Dr Anna Lora-Wainwright (@troverex) 's ethnography of pollution in 3 villages in rural China, "Resigned Activism" @mitpress pic.twitter.com/7vlUrI8Izc

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

Read how @troverex describes a) current state of affairs b) how her work connects w broader themes c) how her work contributes 2 scholarship pic.twitter.com/VrIWG6ggJ3

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

Note how, rather masterfully, @troverex situates her work within similar works to her, HOWEVER she makes explicit how she contributed pic.twitter.com/gwvOR5CUDd

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

I also read an edited volume (“Untapped”) to show how the editors made it clear to the reader what’s the common thread throughout the book.

With Untapped, Chapman and coauthors explore the question of "what is sociological about beer?" pic.twitter.com/tVcf069LRm

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

Note how the table of contents makes it explicit that the book does have a coherent thread that crosses throughout the edited volume. pic.twitter.com/88kUCyF0gG

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

Chapman et al (editors) use a 3 part Introduction model. Firstly, they set up the stage by explaining the emergence and relevance of craft beer global and local markets. Secondly, they explain what is sociological and cultural about beer. Thirdly, they explain the book structure.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

The third book whose introduction I read and suggested be used as a model was Elizabeth Hoover’s The River Is In Us, an excellent multidisciplinary examination of pollution in a community with Indigenous heritage.

3rd example of great introduction is @bluefancyshawl 's excellent (and interdisciplinary) examination of Akwesasne's fight against pollution pic.twitter.com/5aQyGNvPEo

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

Note how it takes @bluefancyshawl less than 5 pages to fully explain 1) the case study's context 2) the research methods she used 3) the literatures she dialogues with and borrows from to build an interdisciplinary framework 4) her main intent with the book (including new ideas!)

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

… a new way of writing and engaging with the local community that you're studying. As @bluefancyshawl writes, "what and for whom we learn" (Hoover 2017, p. 5). Dr. Hoover's introduction is an excellent model for historians, sociologists, anthropologists, urban studies scholars.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

In my Twitter thread I also wrote about Diane Coffey and Dean Spear’s “Where India Goes” and Josh Lepawsky’s “Reassembling Rubbish”. You can go back to the thread by clicking on any of the tweets shown above. I hope this post helps those who are writing their first books or transforming their dissertation into a book manuscript, or even editing their first volumes.

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

Continuing the Discussion