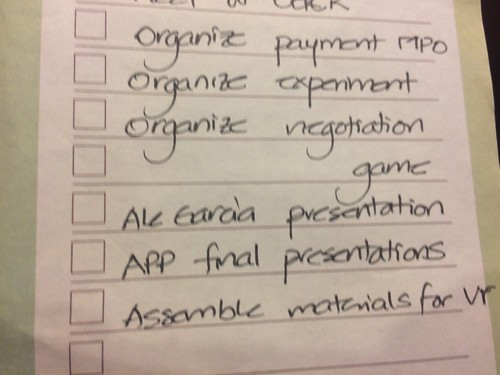

Having a To-Do List, and a schedule of activities, is KEY.

“What then shall I do this morning? How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time. A schedule is a mock-up of reason and order-willed, faked, and so brought into being; it is a peace and a haven set into the wreck of time; it is a lifeboat on which you find yourself, decades later, still living. Each day is the same, so you remember the series afterward as a blurred and powerful pattern.”

– Annie Dillard, The Writing Life, p. 32.

I have witnessed first-hand the havok that NOT having a To-Do List, a list of the items I need to work on and the things I have to do, wreaks on my life. Last year, I found it very difficult to keep track of all the things I was doing. Despite still keeping the discipline of writing in my Everything Notebook and having a broad range of planning strategies, I still struggled.

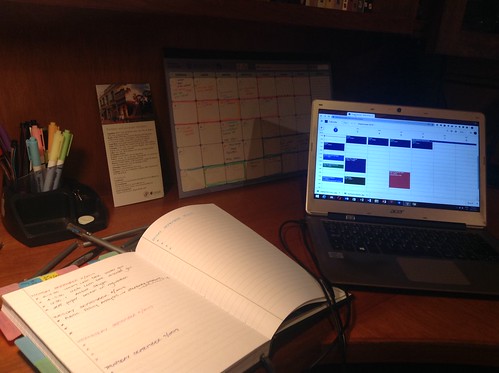

I realized that having everything scheduled on my Google Calendar was still VERY important, but even more so, maintaining a reasonably short, doable To-Do List was key to maintaining my sanity. The calendar gives me a visual overview of what I am supposed to be doing and when I’m supposed to be doing it. The To-Do List I always write it in my Everything Notebook, but also I make a point of ensuring that I have a digital version in case I don’t have my Everything Notebook with me.

Different people plan and maintain a work schedule in contrasting ways. I’ve tried several approaches, including a weekly To-Do List that is visually displayed, preferably on a whiteboard. This method used to be my preferred one, even if it required triple synchronization (Everything Notebook -> Google Calendar -> Office whiteboard). Unfortunately, I no longer have access to a whiteboard, neither at my office at FLACSO Mexico nor at home, so I’ve had to set aside this method for now.

Those of you who have followed me on Twitter/X for a long while or who have read my blog extensively over the years probably know my Everything Notebook-based planning technique. The goal of an Everything Notebook, as I’ve written elsewhere here on my blog, is to keep EVERYTHING in ONE single notebook, rather than having notes here and there and everywhere. It does work wonders for someone like me, who needs to have everything available and at the ready in one single place.

“One of the secrets of getting more done is to make a TO-DO List every day, keep it visible, and use it as a guide to action as you go through the day.”

— Jean de La Fontaine

I always reserve one tab of the Everything Notebook for my Weekly To-Do List.

There are a few lessons that I’ve learned over the course of the years regarding planning, scheduling and developint To-Do Lists. I am listing a few of these here even though I’ve written about them elsewhere on my blog for your easy access and perusal.

1. A To-Do List app (or similar analog system) will not work unless you add ALL your activities to it.

You are a full person (and so am I). This means that the things we have to do for our personal life ALSO take time and need to be considered and accounted for. I used to only schedule my work items in my To-Do List. Big mistake. I can’t plan properly for the future if there are other activities that take up my time, that are absolutely vital and essential for my own survival, and that I am not listing in my To-Do List. And yes, even self-care and rest need to be put in your To-Do List. As weird as this sounds, but making time for myself has been an absolute life saver.

I always include my personal life items in my To-Do List. This includes dentist appointments, doctors’ appointments, and care work. It’s always easy to think that you’ve done nothing when you only get two work-related items in a day because the rest of your day has been taken up by personal life maintenance items. But those are work, too! They are just not paid.

2. Synchronize your To-Do Lists across devices and analog/digital platforms

This is something that a lot of people ask me about when discussing my Everything Notebook strategy. Paper notebooks can feel cumbersome to carry around, and we may forget them at home. So, I always synchronize my To-Do List, including writing commitments, meetings, and other responsibilities.

3. Make your To-Do Lists realistic.

I’ve written about this like a bazillion time here on my blog, but it is really true. I am the king of extra-long To-Do Lists. I want to get EVERYTHING done. And yes, I am single, no kids, able-bodied, with a permanent, tenured job (I’m a Full Professor), so I get that I have a lot of privilege. BUT I also have a natural tendency to overbook myself and think that I can do a lot more than I physically am able to, within the limits of my body.

Whether you use my Granular Planning and the Rule of Threes strategy, or the Accomplish Two Things #2ThingsADay, or your own set of rules, I can certify that it is better to have a manageable To-Do List than an endless array of items that you’ll never get crossed off your list.

4. Actually get through your To-Do List (a Done List is AMAZING):

This sounds a bit weird, I know, but seriously, if you want your To-Do List to work, you actually need to do the things. Every few weeks, I post on all my social media platforms a meme with Peter Parker explaining that to avoid stressing about the things we have in our To Do List, we need to do the things.

“I’ve always made lists of things I want to achieve — it helps me track my progress. But to-do lists are only useful if you do the things on your list.”

— Richard Branson

So yes, as weird as this tip sounds, you’ll feel better about your To-Do List if you actually DO the things. I have always told my students to keep a Done List (the list of what you’ve accomplished, a tip I learned from Dr. Katherine Firth), and a list of Quick Wins. Quick Wins are things you can cross off your To-Do List quickly, that require little effort, and that will help you in the end feel more accomplished.

And at the end of the month, I write a list of everything I accomplished that month.

EVERYTHING.

5. Break down the work in smaller pieces and work on ONE thing at a time, just for 30 minutes at a time:

This is a combination of 3 techniques that I’ve used over the course of my career, from grade school to full professorship: I break down every project in smaller, manageable, workable pieces, and I focus on getting ONE thing done. Even if I can’t finish the entirety of the project or the specific task I am working on, I devote at least 30 minutes to working on that task. And at the end of the month, I write a list of accomplishments and things I got done, and yes that includes every personal item, too.

As I’ve grown older and advanced in my career, I’ve come to realize that most of the challenges we face as academics when it comes to workload is that a vast majority of our time is unstructured and we need to manage multiple projects and deal with a broad range of commitments inside and outside of our institutions. And this is only those of us lucky enough to have a full time job or a well-funded scholarship to do a graduate degree. Precarity in all its forms impacts our careers and our lives in ways that are not always manageable or imaginable. But I hope these strategies that have worked for me may be useful to you all.

Recent Comments